Check out more than a dozen recent titles by faculty—plus books they're reading this summer.

From fiction, memoir, and literary criticism to history, sociology, and technology studies, we rounded up more than a dozen recent titles by Arts and Sciences professors and asked authors to share a book they're reading this summer. (For additional recent faculty books, visit our Faculty Bookshelf.)

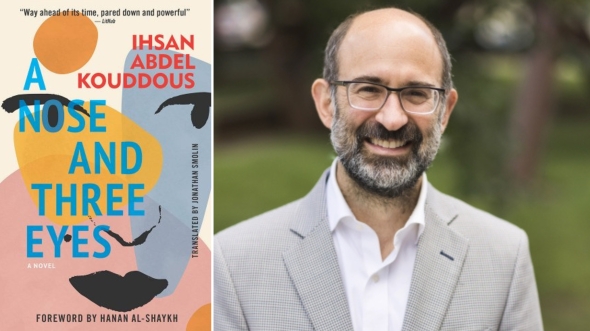

A Nose and Three Eyes: A Novel by Ihsan Abdel Kouddous (Hoopoe)

Translated by Jonathan Smolin, Associate Professor of Middle Eastern Studies

Deeply controversial and wildly popular when first published in serial form in the 1960s, this story of female desire, sexual awakening, and despair made Kouddous the first novelist to be brought before Egypt's parliament under the charges of harming public morality through fiction.

Kouddous was the most popular and prolific writer of Arabic fiction in the 20th century, yet his work has only recently been translated into English. Smolin translated two of Koudouss' novels and also authored the forthcoming The Politics of Melodrama, the first book to consider both his outsized cultural influence and consequential position in Egyptian politics.

"I want the wider English public to discover this brilliant writer for themselves," Smolin said in an interview about I Do Not Sleep, the first novel by Kouddous that he translated. "He was such an innovator, combining elements of the popular press with fiction on a wide scale for the first time in the Arab world. His topics are universal in their appeal—jealousy, desire, rage, regret—but he embedded them all firmly in the historical moment in which he wrote, which was the height of Nasser's Egypt."

What Jonathan Smolin is reading: I'm currently reading Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss What Matters Most, by Douglas Stone, Bruce Patton, and Sheila Heen. This incredible book covers essential techniques for enhancing curiosity, empathy, and active listening skills. It's an absolute must-read in today's climate and provides a fantastic foundation for Dartmouth's Dialogue Project!

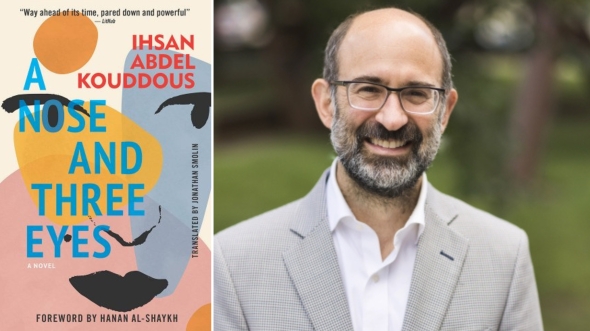

The Incarcerated Modern: Prisons and Public Life in Iran (Stanford University Press)

By Golnar Nikpour, Assistant Professor of History

In just 100 years, Iran evolved from a decentralized empire with relatively few jails into a modern nation state with a vast prison network and more than a quarter of a million incarcerated people.

Nikpour chronicles this seismic shift and how the modern prison gets entrenched so quickly in Iranian society—influencing the lives of ordinary people in consequential ways. She links this transformation with the worldwide trend of promoting carceral solutions—surveillance, policing, and mass punishment and imprisonment—as a response to complex social issues.

"If we take seriously the idea that we would like to see a more just or more free Iran," Nikpour says in an interview about the book hosted by the Rethinking Iran Initiative at the Johns Hopkins' School of Advanced International Studies, "we have to understand the reasons why we are where we are, both in Iran and globally."

What Golnar Nikpour is reading: Locusts of Power: Borders, Empire, and Environment in the Modern Middle East by Samuel Dolbee—A genuinely riveting and pathbreaking environmental history, in which Dolbee traces the importance of non-human actors—in this case, locusts—in the making of the modern Middle East. Locusts of Power is an absolute must-read for those interested in understanding questions of social difference in the post-Ottoman world beyond conventional historiographical emphases on imperial disintegration and the rise of modern nation states.

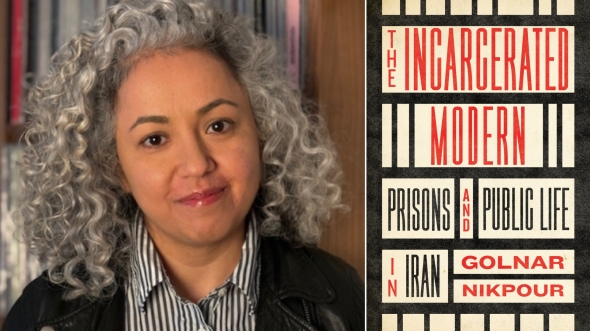

Water on Fire: A Memoir of War (Other Press)

By Tarek El-Ariss, Professor of Middle Eastern Studies

"To read 'Water on Fire' is to peek into the storied soul of a radically optimistic scholar whose skin has been toughened by scars of conflict," Sharon Beriro wrote in her review of El-Ariss's widely praised new memoir in the Brooklyn Rail.

This deeply felt book begins with El-Ariss's formative youth in war-torn Beirut and traces his experiences of growth and displacement in Europe, Africa, and America, concluding in New York City on 9/11.

"For someone like me, war is the default setting," El-Ariss says. "But within these moments of darkness, we have a way of expressing ourselves through games and humor and caring for each other. This is our survival kit."

What Tarek El-Ariss is reading: Iman Mersal's Traces of Enayat poses the following question: How do we bring someone back to life? The story begins when Mersal, a poetess and a professor of literature, picks up a poetry collection by an unknown author called Enayat al-Zayyat at a bookseller in Cairo. Intrigued, Mersal starts the search only to discover that this woman author had committed suicide at a young age in the 60s. Mersal then acts like a detective, assembling fragments and pixels to construct a portrait of Enayat and her community of women that included actresses, journalists, and authors who shaped contemporary arts and culture in Egypt in the 20th century.

Mortevivum: Photography and the Politics of the Visual (MIT Press)

By Kimberly Juanita Brown, Associate Professor of English and Creative Writing

The inaugural director of the Institute for Black Intellectual and Cultural Life traces how documentary photography across cultures and continents equates Black people with suffering and death.

"Mortevivum is the term I have come up with to understand a particular photographic phenomenon: the hyperavailability of images in the media that traffic in tropes of impending Black death," Brown writes. She traces this idea from the earliest images of the enslaved to the latest newspaper photographs of Black bodies, and from the United States and South Africa to Haiti and Rwanda, documenting the enduring connection between photography and a global history of antiblackness.

"Images are not neutral," Brown says. "They exist within structures of hegemony that must be interrogated. We all live in a visual world. The question for me is, how do we live in this world?"

What Kimberly Juanita Brown is reading: The book I'm reading right now is one I try to return to every year: Jazz by Toni Morrison. The novel tells the story of love and betrayal, grief, and dispossession. I read it each year because it tells me something important about craft—the beauty of it—its inherent vitality, and its bonded creativity. It is a writer's novel.

I think Morrison's Beloved is the greatest American novel ever published, and Sula is my personal favorite. But Jazz is Black movement and ethos, Black rhythm and blues. It's the sound of Black life.

Consistent Democracy: The "Woman Question" and Self-Government in Nineteenth-Century America

(Oxford University Press)

By Leslie Butler, Professor of History

"In the American democracy, the aristocracy of skin, and the aristocracy of sex, retain their privileges," John Stuart Mill wrote in his 1836 review of Alexis de Toqueville's Democracy in America.

Like dozens of other foreign observers of America in the 1830s, he was "puzzling through" what's new about American democracy, Butler says in a talk about Consistent Democracy livestreamed by the American Antiquarian Society. "As Americans and foreigners discussed women's rights and responsibilities, they were also thinking through some pretty fundamental aspects of democratic theory: What does it mean to be a democratic people? What does democratic governance mean?"

Butler showcases how "the woman question" ignited a "raucous public discussion" about democracy among 19th-century observers, activists, and thinkers, which she traces across a range of materials, including treatises, advice manuals, etiquette books, short stories, illustrations, and novels.

Ambivalence about making democracy consistent for all adults gained traction in the last decades of the 19th century. "It sort of crystallized as a clear throughline of American history for me—this ambivalence towards democracy is an ever-present strand," Butler says.

What Leslie Butler is reading: I'm finally reading a book that has been on my "to read" list for a couple years: All That She Carried by Tiya Miles. The work centers on an artifact (now on exhibit at the International African American Museum in Charleston)—a cotton sack passed down from an enslaved mother to her enslaved (and about to be sold) daughter in the 19th century and then embroidered by that daughter's free granddaughter in the 20th century. Painstakingly researched and powerfully written, the book offers a poignant musing on intergenerational familial love but also on the craft of history—on the limitations of traditional archives and the importance of empathetic imagination to understanding the past.

In addition to history, I read (and listen to) a lot of fiction. I just finished Percival Everett's James. To say that the novel offers a retelling of Mark Twain's Huckleberry Finn from the enslaved Jim's perspective is accurate but wildly inadequate. Equal parts provocative, hilarious, and devastating, James conjures a rich inner life for its protagonist. The character Jim/James teaches enslaved children how to code-switch when speaking to whites (using the "correct incorrect grammar"), engages in imaginary conversations with Voltaire and Rousseau, and ultimately authors his own complex and fully realized story.

katiehornstein8.jpg

Myth and Menagerie: Seeing Lions in the Nineteenth Century (Yale University Press)

By Katie Hornstein, Professor of Art History

This chronicle of lions in 19th-century painting, drawing, sculpture, and photography melds art history with hints of memoir.

"The book is very, very personal," Hornstein says. "Grief is what sustained this book and gives it the character that it has; I realized as I was writing through the loss of my mother and my cat in the fall of 2020 and the winter of 2021, that I was also grieving the deaths of the historical lions who are the focus of my book and whose lives and images I have studied."

Thanks to Hornstein, many of these lions now have life stories and names—such as Constantine, Jemmapes, Marengo, Fleurus, and Coco—and can be seen as sentient, expressive beings who "lived in a particular time and place, not as timeless, passive objects of representation" for esteemed artists.

What Katie Hornstein is reading: I am reading Being Here is Everything: The Life of Paul Modersohn-Becker, by Marie Darrieussecq and translated by Penny Hueston. The novel is based on archival research into the life of Modersohn-Becker, who was a pioneering modernist painter born in Germany in the late 19th century. The novel tracks her childhood, her transformation into the deeply committed painter she became, and her untimely death after giving birth to her first child. I am very attached to teaching Modersohn-Becker's trailblazing figure paintings, including the very first nude self-portrait painted by a woman, as well as her heroic 1906 painting of a nude mother and a child, so I was delighted when Matt Siegle, a colleague in studio art, recommended it to me.

Equality: The History of an Elusive Idea (Hachette Book Group)

By Darrin McMahon, David W. Little Class of 1944 Professor of History

Darrin McMahon's new book earned him the American Philosophical Society's prestigious Jacques Barzun Prize in Cultural History—for historians, the equivalent of winning the Pulitzer.

Praised as "a landmark work of intellectual history" by Literary Review and "sweeping" and "thought-provoking" by The Washington Post, the book traces the global origins of equality from the dawn of humanity to today.

McMahon considers the book a sequel to his prior books on the history of happiness and the modern fascination with genius. "Equality seemed like a perfect way to complete the trilogy," he says. "Like happiness and genius, it's a big powerful idea with a long history that emerges spectacularly in the 18th century. But I didn't realize what I was biting off when I began. When you ask the question, 'What is equality?' you immediately have to ask, 'Equality of what? And for whom?'"

What Darrin McMahon is reading: I'm reading several books right now, but the one I'd recommend particularly is by the Canadian professor, writer, and politician Michael Ignatieff. The book is titled On Consolation: Finding Solace in Dark Times. It is a deep meditation on the meaning of consolation, using great religious, philosophical, and literary texts from the Western tradition as guides. He's a masterful writer and a tremendously engaging mind. It is an argument unto itself for why the humanities matter. I'm thinking of using it next year in my history of happiness class.

A Politics of Melancholia: From Plato to Arendt (Princeton University Press)

By George Edmondson, Associate Professor of English and

Klaus Mladek, Associate Professor of German Studies and Comparative Literature

While academia has been "slow to acknowledge, let alone reward, collaboration in the humanities," English professor George Edmondson says, Dartmouth offered him and German studies professor Klaus Mladek myriad venues for developing their co-authored book, including a co-taught interdisciplinary course and a special institute presented by the Leslie Center for the Humanities.

In their new book, the pair argue that melancholia is wrongly condemned as a condition of withdrawal and despair. Instead, Edmondson and Mladek champion the melancholic figure as a catalyst for political transformation. Through close examination of ancient and modern texts, they offer new perspectives on such pivotal political moments as the death of Socrates, the fratricide in Hamlet, and the murder of Moses in Freud's last text.

"Our politicized melancholic, far from being indifferent, marginalized, or affectively disciplined," they write, "embodies the universal condition of communal life: a discontent that so vexes and irritates a community's members that it becomes the common symptom binding them together."

What Klaus Mladek is reading: It might seem counterintuitive to suggest Edgar Allen Poe's short stories for summer reading. But there is nothing more riveting than huddling with your friends or family around a campfire and reading out loud "The Tell Tale Heart," "The Black Cat," or "The Cask of Amontillado." The next morning, the still beating heart of the old man, the "imp of perverseness," or the ghastly vision of the howling cat in the wall linger; they make you mull over "the eerie delight in the turmoil of the soul."

The Map in the Machine: Charting the Spatial Architecture of Digital Capitalism

(University of California Press)

By Luis Alvarez León, Associate Professor of Geography

From Spotify and Netflix to AirBnB and Instacart, tech startups rapidly transformed the digital economy over the first two decades of the 21st century.

Alvarez León examines the influence of digital technologies on a wide range of activities—from food delivery to map reading—and how they created new markets and ways to connect with consumers. Ultimately, he argues that the digitization of global capitalism reshaped the geographic organization or "spatial architecture" of the economy.

"Digitization is not only changing how we shop, live, work, play, and communicate," Alvarez León writes, "but in the process, it is also reconstituting the very spaces and places where we engage in all these activities, the interconnections between them, and consequently the way we conceive of, organize, and navigate our societies and economies."

What Luis Alvarez León is reading: This summer I have been diving back into fiction after many years of reading mostly nonfiction and social science books. Two books that captured my imagination are Exhalation by Ted Chiang and Bloodchild and Other Stories by Octavia Butler. Chiang's stories raise both timeless and urgent questions about morality, technology, science, and knowledge, explored through intricately detailed worlds that are both strange and yet so much like our own. Butler's stories—often set in dystopian, or near-dystopian scenarios—on the other hand grapple with the intersectional nature of systems of domination as well as issues of power, agency, and even forgiveness in unthinkable situations. Reading these books has been an exciting way to reconnect with the craft of writing and the possibilities of the literary imagination.

One Soul We Divided: A Critical Edition of the Diary of Michael Field (Princeton University Press)

Edited by Carolyn Dever, Professor of English and Creative Writing

After immersing herself for nearly two decades in the study of the diary of Michael Field, the pseudonym of 19th-century authors and romantic partners Katharine Bradley and Edith Cooper, Carolyn Dever authored two pioneering scholarly books devoted to it.

The first book, Chains of Love and Beauty, champions the diary as a great unknown "novel" of the 19th century and a work that bridges the Victorian marriage plots of George Eliot with the modernist experimentation of Virginia Woolf. And this inaugural critical edition of the diary features the first book-length selection from the 9,500-page, 29-volume work.

"It's hard not to be grasped by their story," Dever says. "They're two women; they're writing as a man. They're aunt and niece; they're also a devotedly romantic couple. Their poetry is spectacular. They knew everybody: Reading these diaries is a "who's who" of late 19th century England, and Europe more broadly. So there's a kind of cosmopolitanism, a thoughtfulness, and an insight about art and culture and identity that comes out so clearly in these diaries."

What Carolyn Dever is reading: A book I'm reading this summer is Gender Without Identity, by Avi Saketopoulou and Ann Pellegrini. This book is an offering of enormous generosity, principle, and respect to people whose "non-normative" identities have been met with neither generosity nor respect in psychoanalytic institutions, some of which attempted to censor the volume in its earlier form as an award-winning article. The authors makes the case for the acquisition of gender through the "spinning up" of experiences, including trauma. By shifting gender formation from a question of "what" to a question of "how," the book offers a radically inclusive way of thinking about the interrelations of experience and identity.

hooley_summer_books2.jpg

Against Extraction: Indigenous Modernism in the Twin Cities (Duke University Press)

By Matt Hooley, Assistant Professor of Native American and Indigenous Studies

Hooley traces a modern tradition of Indigenous literature and art in Minneapolis and St. Paul that emerged from the mid-19th century to the present in response to the cultural legacies of colonialism. He examines the work of five Ojibwe writers and artists, including Pulitzer Prize winner Louise Erdrich '76.

For Hooley, writing "against extraction" means "in opposition to, but also in proximity," he says. "I want to know: How do we read texts that are antagonistic to the structures that make the colonial world seem coherent but that are also produced within it? I'm interested in colonial critique that understands Indigenous writers and artists as experts both of their own tribal cultural and political traditions and as expert analysts of colonialism."

What Matt Hooley is reading: I just finished the first novel by the brilliant Penobscot writer Morgan Talty '16, Fire Exit, which was published this year. It's an engrossing story about how difficult and beautiful it is to care for each other amidst the complexities of colonialism, enrollment, family secrets, and illness. Like his first book of short stories, Night of the Living Rez, Fire Exit is a beautiful and subtle book that richly contributes to the extraordinary tradition of Indigenous creative writers who graduated from Dartmouth.

Messianic Zionism in the Digital Age: Jews, Noahides, and the Third Temple Imaginary (Rutgers University Press)

By Rachel Feldman, Assistant Professor of Religion

Rachel Feldman was conducting fieldwork at a religious event in Dallas when she realized that her research on Israel's messianic right wing would be a transnational undertaking.

The Jerusalem-based Temple Institute was hosting an anniversary celebration and Feldman was shocked to discover that "most of the attendees no longer identified as Christian at all, but rather as 'Children of Noah', or more simply, Noahides," she recalls. "They considered themselves partners in building the Third Temple and bringing the messianic era and they had arrived at this new faith identity through interactions with rabbis from Israel's religious right wing."

To narrate the full story of messianic Zionism in the digital age, Feldman realized she would have to look beyond Israel's geographic borders and consider new evolving connections between Israeli fundamentalists and Christians around the world. Her book also illuminates the complex ways in which both religious and secular liberalism have sustained the Israel-Palestine conflict.

What Rachel Feldman is reading: I am reading Rachel Aviv's book Strangers to Ourselves right now. This is a beautiful meditation on the limits of psychiatry and psychoanalysis told through a series of captivating accounts of individual mental health journeys. An important and thought-provoking read for anyone interested in social constructions of illness and America's mental health crisis that has intensified post-Covid.

cox-web3.jpg

Common Boundaries: The Theory and Practice of Environmental Property (Agenda Publishing)

By Michael Cox, Professor of Environmental Studies

How should communities engage with the natural environment through property rights and responsibilities?

In his first book, Cox brings his passion for synthesizing ideas to rights-based environmental policies and cultural environmental ownership practices. This interdisciplinary approach, which highlights past challenges and successes, lays the groundwork for better responses to environmental problems in the future.

"Academia is fragmented," Cox says. "Maintaining cooperation in an academic discipline involves setting boundaries for who is and is not a legitimate disciplinary member. But this creates barriers to cooperation across disciplines. In this book, I wanted to merge them."

What Michael Cox is reading: The book that I have stuck with this summer has been American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer, by Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin. I was inspired to read it after watching the movie. I sometimes miss feeling like I'm part of a larger team with an important mission, and it's interesting that the academics in this movie certainly had that, but also deeply troubling what their mission actually was, and what consequences it had, which Oppenheimer himself struggled with a lot. It reminds me of a question I've had for a while: Can we inspire a sense of urgency and cooperation without a human enemy to rally against?

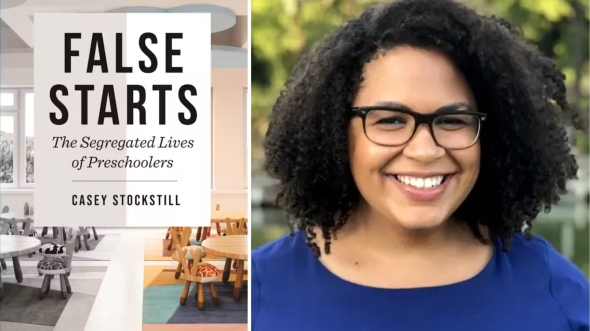

False Starts: The Segregated Lives of Preschoolers (NYU Press)

By Casey Stockstill, Assistant Professor of Sociology

When sociologist Casey Stockstill set out to observe two top-ranked preschools in Madison, Wisc., she didn't expect to discover two markedly distinct classroom experiences.

Her two-year study focused on a government-funded Head Start program designed for low-income students and a private, tuition-based facility serving predominantly white and affluent families. Segregation by race and class, Stockstill discovered, has a profound impact on the ways children spend their time, the instruction they receive, and how they learn.

"I want people to want more out of preschool," Stockstill says. "I think we owe children of color and poor children more than we are giving them—even the ones who get a spot in preschool."

What Casey Stockstill is reading: I'm re-reading a sociology classic, Privilege: The Making of an Adolescent Elite at St. Paul's School, by Shamus Khan. The book is taking on new meaning this time, as my family lives a few miles from St. Paul's School in Concord, New Hampshire. The book gives an ethnographic, critical take on how elite culture has changed.