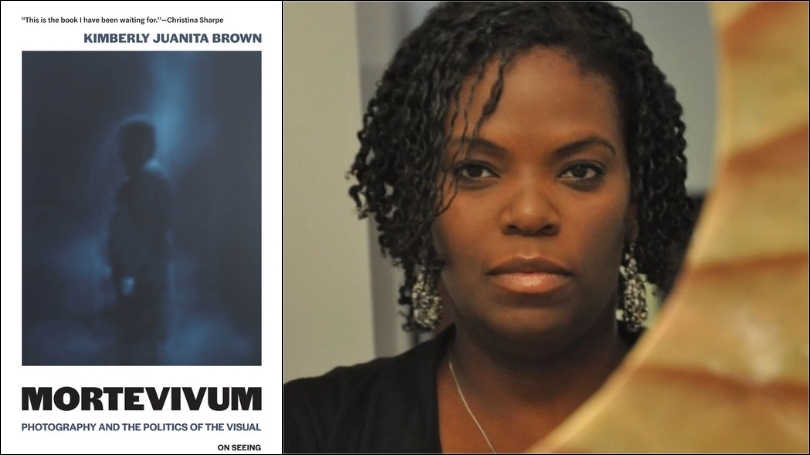

In her new book, professor Kimberly Juanita Brown shows how documentary photography across the ages links Blackness with suffering and death.

Kimberly Juanita Brown has been fascinated by photography since she was a child.

"I'm still drawn to its staticity, its ambivalence," says the associate professor of English and creative writing.

A literary critic by training, Brown works at the intersection of African American and African diaspora literature and visual culture studies. "This combination of visual culture and race was a natural fit for me," she says.

At Dartmouth, Brown also serves as the inaugural director of the Institute for Black Intellectual and Cultural Life, a research center rooted in the study of the Black diaspora.

Her first book, The Repeating Body: Slavery's Visual Resonance in the Contemporary, clarifies how literary texts and images representing Black women's bodies foreground the cruelty and vulnerability of slavery.

In her new book, Mortevivum: Photography and the Politics of the Visual, which she finished during a fellowship at Harvard's Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, Brown narrows her focus to documentary photography. She traces how photography across cultures and continents—from the earliest published newspaper images—equates Black people with suffering and death.

Mortevivum is the inaugural title of On Seeing, a new publication series devoted to visual literacy. The MIT Press will publish each On Seeing volume as a print book, ebook, and open access digital edition created by Brown University Digital Publications. The full digital edition of Mortevivum will be available in June.

In a Q&A, Brown discusses the impetus for the book, its inventive title, what she hopes readers take away, and her follow-up already in the works—the second title of On Seeing, which will be published next February.

Your first book, The Repeating Body, illuminates images of Black women's bodies as records of slavery. How did that project inform this new book?

The Repeating Body allowed me to center my work within and through the apparatus of the visual as it related to slavery. It was a kind of freedom that I needed and that my interdisciplinary training gave me. I went where the images took me.

For this project I hoped to contain the apparatus, to say something distinctive and precise about photography, a genre of representation I have been obsessed with since I was a child. I found a book of Helen Levitt's street photography when I was in elementary school and was instantly mesmerized. There were photographs of children in New York City and they were exuberant and joyous and free and beautiful. It was my first real encounter with spontaneous portraiture. I am much more familiar with fine art photography, so I wanted to deepen my exploration of documentary photographs, where I think there is so much to be said.

"Mortevivum," the title of the book, roughly translates as "death alive" in Latin. How did you come up with it?

I was having a hard time encapsulating the force of the visual on racialized subjects. I needed a term that tethered the history of documentary photography to histories of global antiblackness, rendered through a kind of proximity to death.

The term "mortevivum" seemed to fit the bill. The way that I am defining the term corresponds to photography and antiblackness as "living death in a series of still frames … refusing complex humanity."

Is there an image from the book that comes to mind that gets to the heart of the connection between photography and a global history of antiblackness?

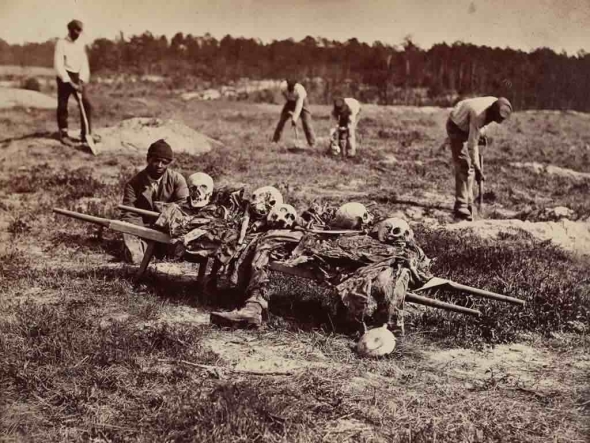

The photograph I continue to refer to in my conversations about the book is a famous image from the Civil War. The photograph appears in Alexander Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War and it was taken by John Reekie. It holds the proximity to death alongside an absence of regard for Black soldiers during the Civil War. I could write a whole book about this photograph.

What first struck me is how staged it is. You can see the Black man seated next to the skulls and bones, and he is not happy about being placed there. I think this photo is supposed to signal to white viewers that white life was sacrificed for Black freedom—submerging all the work Black people did and everything Black soldiers sacrificed. The assumption is that the bones belong to white people who paid the ultimate sacrifice. This leaves viewers with a sense of who is mournable, and who is supposed to be mourned. We have photos of African Americans in service roles during the war, but not many portraits of African American soldiers (on the battlefield). This is what I think about when I see images from the Civil War.

What surprised you most about this project as you conducted your research?

Just how many photographs of dead Black bodies circulate in this country without intervention.

I was struck by how often people notice and speak out when they see graphic images of dead bodies that they think are inappropriate. But when you see a photo of a Black person who is dead, we don't see a lot of people who are not Black writing in and saying, how could you publish this in a newspaper? They just don't have that kind of currency. There's something about the history of antiblackness in this country that does not let people empathize or grieve alongside Black subjects.

I've given talks over the years and I spent a lot of time trying to prove it. And then I stopped because the images were just too graphic. I didn't feel like I could do that kind of harm to the very subjects I was trying to represent. So I stopped showing the images.

What do you hope readers take away from this book?

Images are not neutral; they exist within structures of hegemony that must be interrogated. We all live in a visual world. The question for me is, how do we live in this world?

The relationship that you have with yourself and your interiority and the relationship you have with the outer world is based on perception. That's how antiblackness functions, and how you know what you can get away with. Other people live in this world and notice this less because they are less vulnerable to harm.

You need only to attend to this space to see heightened anxiety around how you're being captured and why—something that everybody doesn't have to think about. This is similar to what women have to think about. There's a heightened awareness of how you move through these spaces and how you're constructed or perceived.

How did this book lead to your forthcoming book, Black Elegies, which will be the second title in the On Seeing series?

Mortevivum and Black Elegies constitute a diptych—they are paired texts that are meant to work together so the reader has a fuller understanding of Black subjectivity in the contemporary moment. Global antiblackness has precipitated an archive of multivalent elegiac responses. I refer to Mortevivum as "the trauma" and Black Elegies as "the release," if that makes sense.

Black people in spaces where white supremacy was prevalent had to hide their mourning rituals by embedding them into something else. For example, sorrow songs, created by enslaved subjects in the U.S., hide grief in tunes about redemption and love of God. They could not plainly say, "I am dying here."

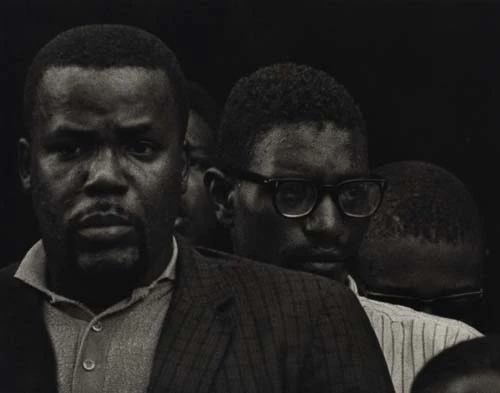

The single image that enables my understanding of what this book is trying to do is a photograph by Roy DeCarava. The image is of four men emerging from a memorial service for the four girls killed in a church bomb explosion in Birmingham, Alabama in 1963. Their faces are a looping circular study of the stages of grief. It feels only right that I examine these elegies alongside graphic images that have circulated for centuries, doing so much harm.