- About

- Departments & Programs

- Faculty Resources

- Governance

- Diversity

- News

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

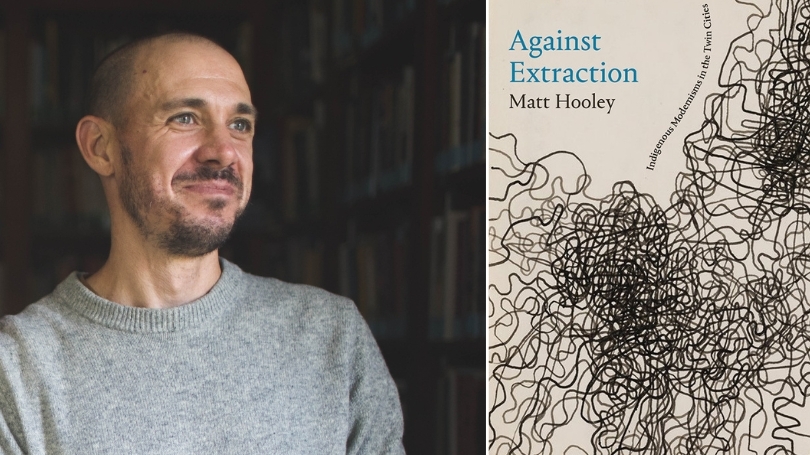

In his new book, professor Matt Hooley analyzes the works of five Ojibwe writers and artists through the lens of anticolonialism.

Matt Hooley was born in Minneapolis, but that's not the only reason he chose to center his book there. The Twin Cities were among nearly a dozen places picked by the U.S. government in the 1950s as "relocation cities" to coerce Indigenous people to leave their tribal homelands and assimilate into America's capitalist society.

The influx of Indigenous people to places like the Twin Cities coincided with an exodus of white people to the suburbs fleeing, in part, pollution and corporate disinvestment. Hooley, an assistant professor in the Department of Native American and Indigenous Studies, examines the cultural legacy of this shift through the work of five Ojibwe writers and artists in his first book, Against Extraction: Indigenous Modernism in the Twin Cities.

The loss of land, along with ties to community and nature, is a dominant motif in the works Hooley covers. But their backdrop is a cosmopolitan city hundreds of miles from Ojibwe homelands in northern Minnesota. This disconnect, says Hooley, makes the Twin Cities an ideal place to think about modernist themes of dislocation and alienation from an Indigenous perspective.

The concept of place is as central to the book as it is in Hooley's classroom. His classes, including Perspectives in Native American Studies, which he is teaching this term, invite students to reconsider their understanding of where they are.

"Thinking about land is a good way to remember how artificial the forms that give our lives shape are," he says. "The university is not land. The university is occupying land. The university may seem like a real physical place with a deep history, but it's a construct."

The modern world is full of such constructs, Hooley says, and Against Extraction represents an attempt to illuminate them.

In a Q&A, Hooley reflects on what it means to write "against extraction," his engagement with novelist Louise Erdrich '76, and how the history of colonialism informs modern approaches to fighting climate change.

What does it mean to write against extraction?

I was tempted to call this book "literary decolonization," but it isn't about dismantling colonialism or even making it kinder. Instead, writing "against" extraction means in opposition to, but also in proximity. I want to know: how do we read texts that are antagonistic to the structures that make the colonial world seem coherent but that are also produced within it?

You begin and end with the visual artist George Morrison. Why?

Morrison gives literal shape to the practices and questions motivating the other writers in the book. Morrison's collages are made of fragments of wood he found all over the country that he brings together into massive landscapes. I argue that they are pieces that literally make land—a gesture that isn't present in European or American modernism.

This is a book about extraction and commodity subjects and objects. These pieces of wood were once trees cut into forms to be used in commercial settings across the world. What's lost in moving from a tree to a two-by-four? You could say: the relation to land. In these landscapes, Morrison brilliantly brings these ideas together. We don't necessarily see land literally, but we can't describe his work in extractive terms anymore either. They're no longer two-by-fours.

Is this what you mean by Indigenous modernism?

I think he's critiquing industrial capitalism, as most modernists are, but he's also doing something generative. He's remaking relations out of fragmentation and loss. I think this is characteristic of what I'm calling Indigenous modernism.

When does Indigenous modernism begin?

For me it's 1887, when the Allotment Act was passed. It privatized tribal land into individual holdings and made them taxable. It also made it much harder for tribes to hold onto land. No U.S. law has produced a greater dispossession of Indigenous land—more than 100 million acres in 30 years. It was a catastrophic shift. It's one of the ways American cities got built. It opened natural resources to extraction and produced an urban wage-labor force. It was meant as a well-meaning reform.

Allotment is at the center of this book because colonialism violence comes in many forms—the massacre, the epidemic—but it also comes in more insidious ways, like well-intentioned aid.

You also focus on Pulitzer Prize winner Louise Erdrich '76. How does her writing embody Indigenous modernism?

Her tribal homelands are in North Dakota now, but she's lived in Minneapolis for many years and owns a bookstore there, Birchbark Books, that's a hub of intellectual life.

The protagonist of the two novels I write about, Tracks, and Four Souls, is a woman named Fleur. A logging company takes her land and seizes her trees. She walks to Minneapolis and infiltrates the house of a logging company executive. In one scene, she reflects on her connection to the actual material of his house. Erdrich is critiquing the English domestic novel, but also, by centering Fleur's relationship on the literal material of the house, she focuses on a different kind of domesticity: Fleur's kinship with land. Fleur is with her trees in a way that's unlike any other modernist novel.

You are not Indigenous yourself. What led you to this field?

I'm interested in colonial critique that understands Indigenous writers and artists as experts both of their own tribal cultural and political traditions and as expert analysts of colonialism. Rather than focus on European ideas, I want to begin with Indigenous texts and critique colonial structures from their perspective.

Dartmouth also has a special relationship to Indigenous studies. Native students have come here from all over the world. It's a great honor to be able to learn with them.

How can this work help us to think about environmental crises, including climate change, differently?

We have a bad habit of talking about the climate crisis as a singular event. But if you look at the history of colonialism from an Indigenous perspective, climate crises are recurrent. So much of our political discourse is about trying to stop climate change or escape it. The history of colonial climate crises suggests that the better question to ask is, how can we live through it?

The third chapter of the book is about a novel set during relocation. Minneapolis is suburbanizing, and rich white people are fleeing the aftermath of industrialization. The suburbs offered an escape. Indigenous relocation, by contrast, repopulated cities with a wage-labor force to live amid the poisoned water and soil left by industrialization—something we still see today. There's a climate crisis in Flint, but the Black and Indigenous residents of Flint are not escaping it, they're living and dying with it.

Indigenous people all over the world have had to do this. When we think about the environment, colonialism should always be addressed. Magical technological solutions won't work. The climate "crisis" will end with the end of colonialism.