- About

- Departments & Programs

- Faculty Resources

- Governance

- Diversity

- News

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

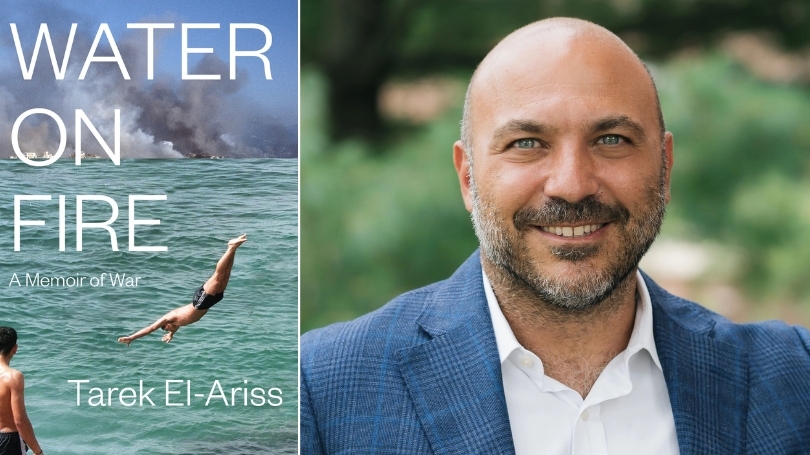

In his new memoir, professor Tarek El-Ariss revisits Lebanon's civil war and a childhood marked by tragedy and unexpected moments of beauty and joy.

One day during the pandemic, as Tarek El-Ariss was moving offices at Dartmouth, a book fell off the shelf. Out fell a note from the doctor he had gone to see decades earlier for a mysterious skin condition.

"My skin got so dry it felt like I had these insects devouring me, like in a Dali painting," says El-Ariss, the James Wright Professor and chair of the Middle Eastern Studies Program, who with colleagues there and the Jewish Studies Program also leads the Dialogue Project's special topic series on the crisis in the Middle East.

The doctor's diagnosis was far less dramatic. "A delusional infestation," the note read.

During the years of therapy that followed, El-Ariss would uncover its source: the repressed memories of a childhood lived amid Lebanon's civil war.

In his new book, Water on Fire: A Memoir of War, El-Ariss wrestles with memories of the past and the nature of identity, and his epiphany that the war never really ends. The psychological wounds reopen with each new conflict, the ongoing Israel-Hamas war in Gaza included.

El-Ariss sat down to write the penultimate chapter of his book, "An Erie Canal," on the day he rediscovered his old doctor's note. Much of the book, he said, came out this way, triggered by a series of fortuitous events.

"It's like a door opens in the bookshelf and you enter through a portal," he says, speaking from his new office, framed by rows of books and the cover of his memoir. "This is how memory comes, like a book that falls off the shelf."

In a Q&A, El-Ariss discusses the impetus for the book, his writing process, and advice for those who have been touched by war.

What prompted Water on Fire?

I was writing a book on monsters and mythical figures, and how myth is coming back in modern times, and then Covid happened. The monster was now this mysterious virus about to decimate humanity. During Covid, the experience of confinement, and the anxiety about whether we would have enough water, food, or necessities, brought me back to the war in Lebanon: The civil war, which lasted from 1975 to 1990; divided my city, Beirut, into two waring sectors; and led to interminable sieges and shortages at various moments of the protracted conflict that drew in powers including Syria, Israel, and the United States.

Immediately I sat down and wrote the chapter, "Sediments," which was about how we bought water, and carried water in plastic containers, during the war. When the pandemic descended on us, I was faced with my moment of mortality. I realized that I could die without telling my story. This is when the memoir, which normally comes later in life, became urgent.

You open with quotes by Job, the Old Testament prophet, and Bruce Lee, the great Hollywood martial artist. Why these two?

In a way, these are the two poles that structure my psyche—the tragic Cassandra, Lady MacBeth, and Job, on the one hand, and on the other, Bruce Lee, who says, "Be like water, my friend," which I interpret as: adapt, flow, fly. There is lightness in the material, and that's why the title of the book is "Water on Fire."

The fire burns you. It's the fire of hell, punishment, and war. But there is also water, where you float and dive, that's blue and reflective and beautiful. How do we bring these elements together within us? Because we can't be entirely on one side or the other. We have to coexist with both: the heaviness and the lightness. Water can also be crushing and destructive as in tsunamis and floods, while fire can warm us, especially in the cold winters of upstate New York and New England where I end up living.

Did you know water would be so important?

Yes, because the first chapter I wrote was "Beachcombers," before I knew there would be a book. It was the first time I published something personal, aside from the poetry I wrote in high school when I had a lot of angst. I wrote my first poem after my father died—in French! Plus d'espoir. "No more hope!" I was 15.

What was the hardest part of writing this book?

The hardest part was to go back to my childhood and capture experiences of great anxiety and fear. To reinhabit the child that was carrying those water containers, not sure if school would be open the next day, who had to move from one place to another because of bombardments. How do you go back and haunt that child, or allow that child to come from the past and haunt you in the present? How do you coexist or visit each other without overtaking each other? This is so hard for a literary critic who analyzes, organizes, and breaks things down. I had to go back to be the character in my own story and to understand what that child was going through.

Did it feel like a throwback to all those years in Freudian analysis?

It's very much like that, but in psychoanalysis you have guidance. Someone is holding your hand. Here, I was alone. The patient and the therapist at the same time.

In the book you describe therapy as a "process of exorcism." Was writing this book like that, too?

It was absolutely an exorcism. It was extremely painful and difficult to listen to these voices. In the chapter on food, "A Boiling Cauldron," I knew I wanted to write about mfattqa, which is a sweet rice pudding with turmeric and tahini. In Arabic, the word means "the craved one," or "the ripped one." That chapter came to me as a sentence: "Her name was Shafiqa." I started hearing it over and over, almost as if there was a ghost talking to me, saying, "Hey, you need to tell my story. I'm here! You don't see me, but I'm present!" It's my memoir but it's also a memorial and a memoir for all those who touched me, and what they went through. It's a personal story and a collective story.

What was the writing process like?

When I start writing I need to disconnect from the world, the social, and even the people I love. I can't be fully there for them. Writing is like a jealous lover. It doesn't allow any competition. It doesn't allow you to be shared with anyone or anything else if you want to get to those moments and kernels that will enable you to uncover something meaningful and informative. I'd go to cafés, my office at Dartmouth, my home, but basically I had to be with the writing all the time and I had to go where it was taking me. The writing imposed on me its own rhythm. It says, "you have to stay with me."

Did it take you anywhere unexpected?

Yes, the "Boiling Cauldron" chapter took me to the famine during the first World War, which also marked the end of the Ottoman era in Lebanon. We read about it, and saw it in a musical on Independence Day, but beneath the happy song and dance is this major trauma that was never really commemorated. I found myself writing about my dad and his favorite dish, mfattqa, and his relationships to his aunt and mom, and suddenly I understood that mfattqa is from the famine and the kitchen of the first World War. It was made to treat those who were emaciated and dying.

The memoir ends on 9/11, and its publication coincides with a new war in the Middle East. What's going through your mind?

The question of war, and how it affects us, was in a sense answered in the chapter on 9/11. The war came back, not only in the destruction in lower Manhattan, but as an experience that pulls you from where you think you are sheltered, into the open battlefield where you have no protection at all. Oct. 7 is the same, an unraveling of this sense of security, of having left, escaped, survived, and found shelter.

You are brought back to the trauma and anxiety, and that place you thought you left behind. It's a kind of toxic lover that doesn't allow you to go. To leave home, adapt, and adjust, you learn how to compartmentalize and say, "I am here. I am not there. I am fully here." But when something like this happens, it messes with the compartmentalization that allows you to live here, in a place outside of war. And then you realize: there is no place outside of war. It's something you have to live with always.

What advice do you have for those touched by war today?

Part of me feels that humanity always finds a way to overcome, even in the darkest hours. The human will for survival and play is so powerful, no war can ever crush that. This is where my hope lies, not particularly in some political solution, because I'm a product of cycles of wars and violence. For someone like me, war is the default setting. But within these moments of darkness, we have a way of expressing ourselves through games and humor and caring for each other. This is our survival kit. This is what the child does, and it gives me hope. Yes, we carry the wounds of these conflicts for the rest of our lives, but we can also develop strategies to live with them.