- About

- Departments & Programs

- Faculty Resources

- Governance

- Diversity

- News

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

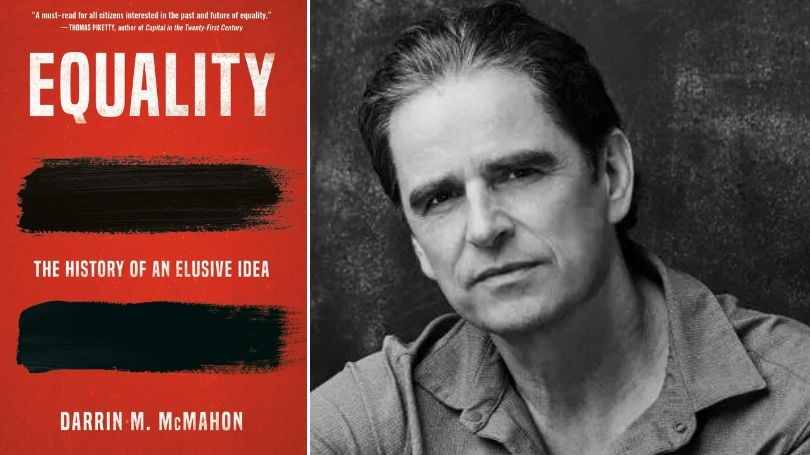

In his new book, Equality: The History of an Elusive Idea, historian Darrin McMahon illuminates how demands for equality throughout the ages have resulted in hierarchy and exclusion.

Darrin McMahon's new book on equality took eight years to write, but in some ways the idea has been percolating in his head since junior high. Everything you needed to know about the social pecking order at his school in Monterey, Calif., in the 1970s, could be inferred by the location of your locker: Jocks on one tier, nerds on the other, everyone else in between.

"It's a model for the way that human beings strive to be both unequal and equal at the same time," says McMahon, the David W. Little Class of 1944 Professor, and chair of the Department of History.

This paradox is at the center of his latest book, Equality: The History of an Elusive Idea, which traces the evolution of equality in theory and practice from hunter-gatherer days to the present. It's a kind of sequel to McMahon's prior two books on the history of happiness and the modern fascination with genius.

"Equality seemed like a perfect way to complete the trilogy," he says. "Like happiness and genius, it's a big powerful idea with a long history that emerges spectacularly in the 18th century. But I didn't realize what I was biting off when I began. When you ask the question, 'What is equality?' you immediately have to ask, 'Equality of what? And for whom?'"

The complex motivations behind a concept that seems deceptively simple on its face became apparent while McMahon was writing his book. The MAGA movement emerged, followed by Me Too and Black Lives Matter. The demands for equality that defined each movement still reverberate today, even amid evidence of widening inequality in the U.S. and abroad.

"The stakes got higher," he says. "Suddenly, this book wasn't just an academic exercise."

In a Q&A, McMahon elaborates on his inspiration for the book, how equality has regularly served as a basis for exclusion, and why as "animals with a history," we can't ignore our basic biology.

Where did you get the idea for this book?

I became interested in the concept of equality while researching Divine Fury. I came to see that the genius figure, which emerges as a new kind of cultural hero in the 18th century, served as a foil to equality. The genius filled the role that saints, prophets, and angels occupied for most of human history. They're endowed with superhuman powers and stand in opposition to the new democratic ideal that all humans are equal. Geniuses are one in a million. They're an antidote to the equalizing, leveling threat of modern culture. Thinking about that got me thinking about equality.

Equality is celebrated in all cultures, yet we're deeply ambivalent. Why?

We are contradictory creatures, and you can observe this ambivalence everywhere once you open your eyes to it. On the one hand, we are hyper aware of our status vis-a-vis others and we strive to rise above. But on the other hand, we tend to resent those who do so. Marketers and others who think about status understand this, but in democratic cultures, we're uncomfortable with it. We bridle at the desire of others to dominate us. The Chileans have this word, chaqueteo, to describe the impulse to take someone by the lapels and pull them down to size. The Australians have 'tall poppy syndrome' to describe the desire to level those would rise above. As a species, we resent those who get a leg up on us. We gossip about them, but at the same time, we're fascinated by them. This human contradiction plays out in the history of equality from the very beginning.

Does Equality have a key takeaway?

I didn't write this book with an axe to grind. I was intrigued by the concept, and the more I thought about it, the more complicated it got. I did an interview with The Nation recently, and their headline was "The History of Equality: It's Complicated." That's it! Honestly, if there's one through line, it's that equality has regularly served as the basis for hierarchy and exclusion. We're all under the spell of this idea that equality is working itself out. Eventually, we'll get to full equality. But more often, equality claims are the basis for assertions of inequality. That's a powerful insight, but not an uplifting message.

You argue, in fact, that inequality is baked into our DNA.

I know it's controversial. Today we talk a lot about the plasticity of human nature. But I think it's naïve to assume that we're animals who can completely remake ourselves and ignore our basic biology. We are animals with a history. If you believe in evolution, it should be clear that we're profoundly connected to the great apes. And the great apes are intensely hierarchical creatures. I think there are lessons there for human beings, even if one has to tread very carefully. There's a long history of researchers, and above all men, using the study of primates to justify all kinds of unsavory things. That's not my intention. And yet, when I watch documentaries about chimpanzees and bonobos, I'm just astounded. I spent eight months during my Guggenheim fellowship working on this material because it seemed so important.

Did your research turn up any surprises?

Everyone is familiar with the Declaration of Independence, and its claim that all men are created equal. I knew that the Greek and Roman stoics believed in universal equality, but I had no idea it was so pervasive. The early Christian rhetoric of equality is quite profound. Yet, at the same time, slavery was fully accepted. Pope Gregory the Great asserts that all men are created equal but at the same time, he owned slaves, as did Thomas Jefferson. To them, it wasn't a contradiction. God created us equal, but we sinned in the garden of Eden, and therefore we live in a world of domination and hierarchy that will only be resolved in the afterlife. What I try to show is there's this long history of people asserting the two things at once—equality and domination—and so it's not so surprising that in the 18th century you have declarations of equality and stark inequalities of race, gender, and class.

You thank your students by name in the book. How did they contribute?

I had a whole number of wonderful research assistants and students who helped me in different ways. I also taught a seminar on equality at Dartmouth. I try to teach classes around the books that I'm writing to think through the material with the students. The discussion was hugely helpful. The students even organized an exhibition, Coeds & Cohogs, on Dartmouth going co-ed in the '70s. The exhibition coincided with an alumni event so students from that first class of women got to see it in person.

If equality is a myth, can it ever be fully realized?

I wouldn't say it is a "myth," but as my title hints, it's certainly elusive. Somebody like Martin Luther King Jr, understood the forces of injustice but he still had faith that we could overcome them. I admire that faith immensely, but in the end I'm more pessimistic about where we may be heading; I'm not sure the arc of history really does bend toward justice. Still, one thing my book shows is that human beings, historically, have demonstrated a tremendous capacity for reinventing and reimagining equality. We'll likely continue to do so going forward.

You deliberately chose not to write a book about inequality. Why?

We live today amidst what has been called an "inequality paradigm." We see inequalities everywhere, and that has focused a lot of research and attention. That is important work, but it can also be distorting. If we only look for inequality, that is all we will see. I hinted above that I'm somewhat pessimistic by nature, but I also believe optimism is a virtue.

I teach a course at Dartmouth on happiness, and one of the things the students learn is that you can't get to happiness just by removing unhappiness. You have to work on both. I'd say something similar about inequality and equality. If we try to better conceive equality—and study how human beings have done that through the ages—perhaps we can better imagine it for the future.