- About

- Departments & Programs

- Faculty Resources

- Governance

- Diversity

- News

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

What happens when we train computers to see the world, when we know they will be influenced by the biases and assumptions of the people who created them? The latest book by professor James Dobson takes readers back to the Cold War-era scientists who taught computers how to see.

From powering surveillance systems to identifying family members in our personal photos, computer vision is a pervasive force in our everyday lives. Technologies that use computer vision are even changing the way we see, as anyone who has come to rely on a car's backup camera—rather than looking over their shoulder—knows.

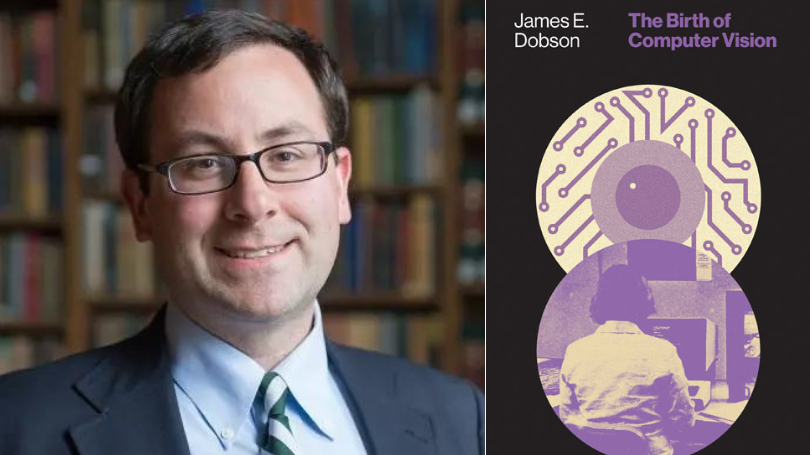

But while we might think computers perceive the world with pure objectivity, the algorithms, methods, and techniques used in computer vision bear the vestiges of the people who created them and the moment in which they were created, as Assistant Professor of English and Creative Writing James E. Dobson shows in his new book, The Birth of Computer Vision.

The book goes back to the 1950s and '60s era of computer development and explores the choices made by engineers and scientists, and how their biases persist in technology that we use today.

In a Q&A, Dobson, who also serves as the director of the Institute for Writing and Rhetoric (and goes by "Jed"), reflects on how culture becomes intertwined with computer methods, the potential risks of image-based artificial intelligence, and the importance of the digital humanities.

What inspired you to write a genealogy of computer vision and machine learning?

My previous book was a critical reading of text analysis methods. For the last chapter of that book, I was researching the history of a machine-learning algorithm used in text analysis called "k-nearest neighbors." I learned a lot about the originators of that method—where they were working, why they developed this k-nearest neighbors algorithm. And it got me interested in what other machine-learning methods also originated back in this Cold War period.

I discovered some of the figures that I wrote about, and I was also looking at a lot of the stuff happening in computer vision in the present. I used an OpenCV computer vision package to guide me backwards. I worked from: What are the most popular methods? Where did they come from? And I used those that were in OpenCV and worked backwards, and then followed the genealogy from there.

Your book also tells the stories of the individuals who were behind these methods. What did you learn from digging into the decisions they made?

I learned a lot about the intersections of politics, universities, and military research in the middle of the 20th century. Frank Rosenblatt, the Cornell computer scientist, was the most interesting of the figures I wrote about, and I have a new book project that's going to be centered on him. Because you could see in his work, and I think it came out in some of the Stanford folks, too, a sense of growing discomfort as we moved from the immediate post-World War II context through the 1960s into the Vietnam era—a sense of growing discomfort with the things that they were being asked to design and implement. The Mansfield Amendment in particular made it a fact that anything produced with DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) funding had to have a military use.

So that drastically changed some people's interests. Others just went along with it and said, "Great, I'll continue to find better ways of bombing." Others changed their mind. Frank Rosenblatt, in his final years as part of this AI War study group, really saw his earlier work, I think, as deeply embedded in a system that he was now wanting to distance himself from. I found that useful—looking at where they came from, who they were funded by, how that shaped their interests. Part of the humanities aspect of the project was to think about the culture that these folks were embedded in.

Recently there were news reports that the latest version of ChatGPT could view images and build things based on those images, such as building a website based on a simple sketch. What are the ethical concerns related to this new ability?

OpenAI's multimodal linking of text production and text analysis with an image—analysis and generation—is provoking all kinds of questions. What happens when we train computers to see the world, when we know they will be influenced by the biases and assumptions of the people who created them?

We've added to that now the complexity of constructing new worlds, as it were, from the world that's seen, further abstracting the sense that there's no bias or there's no particular positioning of the computer that sees the world that's now created. So your example of someone who sketches out a website that is then created—we're both seeing the world in a very particular, situated way, but then creating something from both the position of where we saw that image and also now the text-based world as well. That's going to create all kinds of issues.

Do you think those issues are most likely to arise within the spheres of surveillance and policing? Or do you see the use of this technology as becoming so widespread that it could cause problems we don't even expect?

What came to mind immediately with the announcement about the image and text-based capacities of GPT-4 was the image of someone taking a photo of their refrigerator and saying, "Well, what can I make from this?" That's a great place where culture and methods are all coming together, and this is a simple example, but what sort of foods and cuisine are imagined?

We're obviously going to see the positioning of these technologies in everyday life. You're going to tell me I can make certain kinds of foods that are dominant types of foods from these ingredients and maybe not think about my preferences or other possible cuisine types.

All the ways in which these technologies are involved in world creation—seeing what's involved in surveillance and policing, reinforcing certain understandings of what a norm is, what's accessible, what the assumed audience is for something—will emerge. And the kinds of website design that we're seeing coming from that sketch probably won't address all of the possible viewers of that website.

In the book you write, "It would not be incorrect to say that the deep wish of computer vision is to render vision fully objective and detached from human perception." What would it mean for humanity to have vision that is fully detached from human perception?

I think that taking away uncertainty in all the things that we're confronted by, such as having to make choices between things, whether we're going to go in a certain direction or even to eat a strange fruit that we can't identify—that sort of detachment will probably remove some of the color of the world. Less sense of uncertainty takes away lots of serendipitous experiences or mistakes, but it does decolor the world in some way. I find that an ominous threat of some of those technologies. It also removes some sense of freedom—some freedom to play with the uncertainty of the world.

Your academic interests include subjects found within traditional English departments, such as 19th- and 20th-century English literature, but a lot of your recent work falls within digital humanities and even explores topics in science and technology that might be considered further afield. Do you see the digital humanities as bridging any perceived gap between literary studies and the digital world, and as opening up new ways for the humanities to be relevant?

The digital humanities are one way of making sense of my serpentine career. The digital humanities name a set of intellectual investments and methods that bridges those gaps. I was just meeting with a student this morning, an undergrad, who said he had no way of linking his interest in queer theory from the humanities and sociology with his work in computer science and in our data science-like major that we call QSS, Quantitative Social Science. He had no way of doing that and saw the digital humanities as one way of bridging those gaps, so we had a really good discussion about possible projects and ways of working together.

Prior to earning my PhD in English I was located in a psychology department, so that's why I have some early publications in computer science and neuroimaging. I decided I wanted to do very traditional humanities research, and then wound up bridging some of these interests.

I think the digital humanities are one way of making the humanities relevant at a time when computational culture lacks the sort of critical perspective that is ingrained in the humanities. So it's not only a way of making the humanities speak to our students, but also incredibly important for our present moment: having people with the training and expertise to be able to think about the historical context of these methods and tools. It's essential.