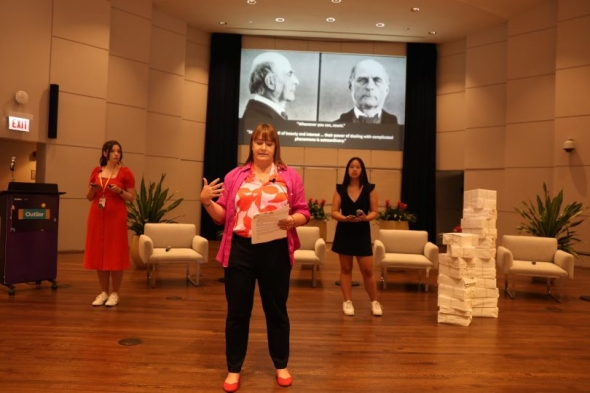

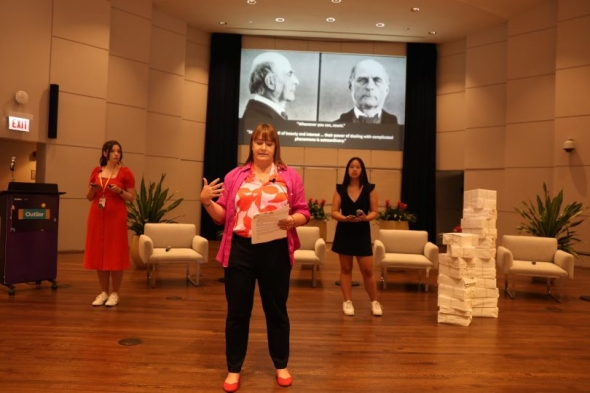

Professor Jacqueline Wernimont, Jane Huang '25, and biomedical informatics specialist Carly Bobak show how creative data visualizations can inspire social change.

Jane Huang '25 was so inspired by her experience last summer as a research assistant to professor Jacqueline Wernimont and biomedical informatics specialist Carly Bobak that she sought out an opportunity to present some of their work at a national conference.

This June the three traveled to Chicago to deliver a mainstage presentation at Outlier, an annual conference that brings together data visualization experts across professions to "stretch our vision of what we can do with data." The 2024 conference focused on "positive disruptors"—those who challenge the status quo in pursuit of positive alternatives.

"Outlier features practitioners who are leaders in the field of innovative data visualization and storytelling, who are really pushing the vanguard of that space," says Wernimont, distinguished chair in digital humanities and social engagement and associate professor of film and media studies. "It's so exciting that we were selected, all thanks to Jane's passion and initiative."

Huang discovered the conference through her association with the Data Visualization Society and took the lead on pitching the team's presentation, which draws on the Eugenics States project, a digital resource Wernimont launched in 2017 with UCLA professor Alexandra Minna Stern and support from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Based on the patient records of more than 60,000 survivors of sterilization procedures in California, Iowa, Michigan, North Carolina, and Utah, the project makes a mostly unknown history more visible through digital storytelling.

Eugenics, the practice of limiting or shaping human populations through sterilization and other forms of reproductive control, was widely institutionalized in 20th-century America, where most sterilization procedures took place at state asylums and hospitals. Thirty-two states had sterilization laws, with California contributing to a third of total national sterilizations—and informing Germany's 1933 eugenics law.

"This is a story that has been covered up incredibly well," Huang says. "The constant association of eugenics with Nazi Germany has meant inadvertently that American eugenics is something people aren't aware of. The legacy of eugenics is much closer to our present than many realize."

In recent years the Eugenics States team expanded into a multi-institutional, interdisciplinary research effort based out of the Sterilization and Social Justice Lab at the Institute for Society and Genetics at UCLA. Wernimont recruited Bobak, who recently completed her PhD in quantitative biomedical sciences at the Geisel School of Medicine, to join the lab and help create data visualizations of sterilization records from multiple states—using a HIPAA-compliant database to protect patient privacy.

A public-facing Eugenics States site is slated to launch in the fall.

"We are particularly interested in how data storytelling can go beyond graphs or visuals to recognize human narratives," says Wernimont. "And we want to put the attention not on the people who were harmed, but on what the data tells us about the people who did the harming and built their careers on it."

"The only documentation we have about the victims are patient records written by doctors who probably wanted to sterilize them," adds Huang. "Let's shift our focus: Who is at fault for this? We can more accurately draw conclusions about the perpetrators than the victims."

'Empathetic' data visualizations

For the Outlier presentation Visual Narratives: Sexual Stigma in Physician Notes From American Eugenics Records, the team used natural language processing techniques to analyze the linguistic choices in doctor's notes that justified recommended sterilizations—and their effects on perpetuating gender biases in the context of sterilization practices.

They focused on 22,511 recommendations and other files associated with sterilization procedures that took place at California institutions between 1921 and 1953—the first 20,000 of which Stern had stumbled upon in a filing cabinet in an abandoned medical facility.

"The language shows how state officials and medical supervisors saw the people that they were sterilizing," Wernimont says.

In creating visual timelines of eugenics supervisors and their language, the team highlights major themes such as the tendency to label patients identified as female as promiscuous and irresponsible mothers. Patients labeled as male were described as disciplinary problems and in terms of perversion, language historically used to stigmatize male homosexuality.

As part of an independent study with Wernimont this past spring, Huang familiarized herself with the work of Francis Galton, one of the first proponents of eugenics, who is also recognized as one of the earliest proponents of statistics and data visualization.

"Both of these movements are rooted in the idea that if someone can be quantified, we can understand them better and make better decisions," she says. "This project is about breaking out of the mindset that everything can be represented with numbers."

For example, a 10-foot stack of paper serves as a visual for the number of patient medical records, a paltry representation of the more than 22,000 people represented in the records.

"The idea is to give a sense of scale," Huang says. "At the same time, it shows how people are minimized into data and statistics. Their rights over their own bodies were taken from them and they've been reduced into a stack of paper."

Huang also studied the trend towards "empathetic data visualization" and the work of the influential information designer Giorgia Lupi, who popularized the idea of "data humanism" and the recognition that people are more than data.

"We want to demonstrate that data visualization has the potential to not only inform but also inspire action and advocacy for social justice," says Huang, who is working with Bobak as a data science summer associate and plans to continue collaborating with Wernimont on the eugenics project next year.

She calls the possibility of eugenics reparations "a relevant and pressing issue," noting the recent programs in a few states, including California, to compensate victims of forced sterilizations as a result of the work of the Sterilization and Social Justice Lab.

"Eugenics manifests in subtle, often unrecognized ways, perpetuating racism and misogyny," Huang says. "It is crucial to understand that these practices could re-emerge and, in many ways, continue to persist today."