Professor Mark Laidre curated a new exhibit on animal architecture that includes the coconut crab, the subject of a new four-year study.

To fully appreciate a termite mound, you have to measure its size relative to its creator, says Mark Laidre, an assistant professor in the Department of Biological Sciences.

"At termite scale, a termite mound is taller than most skyscrapers," he says. "Many animals have been acting as architects by constructing shelters and other structures for hundreds of millions of years."

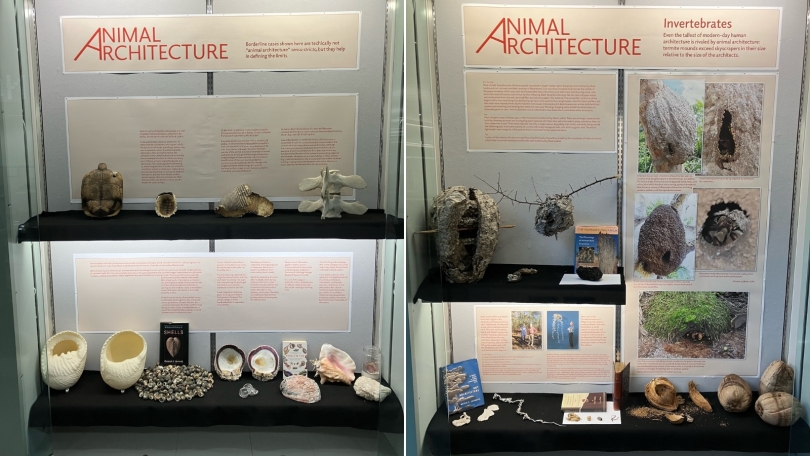

Laidre explores the built environment from an animal-based perspective in a new exhibit, Animal Architecture, on display at Baker-Berry Library until March 29. From beehives and bird nests to remodeled shells of all shapes and sizes, the exhibit looks at the many ways animals alter their environment to suit their needs.

The exhibit connects to Laidre's class this term, Social Evolution: Cooperation and Construction Among Animal Architects, and his ongoing research on coconut crabs.

The coconut crab is one of dozens of species of hermit crab to live on land. But in other ways, it stands in a class of its own. The size of a small carry-on bag, the coconut crab is the largest land-based invertebrate on the planet. It can crack open coconuts with its bare claws, ingest poisonous plants without getting sick, and forage along windswept beaches with only the thinnest of bodyarmor.

"The coolest thing is to see them walking around shell-less with this fully recalcified abdomen and an almost alien-looking carapace which contains their breathing apparatus," says Laidre.

Charles Darwin commented on the coconut crab's "monstrous" size on a layover in the Indian Ocean during his five-year voyage around the world aboard the Beagle. But despite its fearsome appearance, the 10-legged arthropod faces an uncertain future. It thrives on remote tropical islands threatened by climate change and rising seas. In addition to habitat loss, other pressures on coconut crab populations include overharvesting, and what Laidre, an expert on terrestrial hermit crabs, calls a "challenging housing market."

More Shells, More Crabs?

Shells are essential in the coconut crab life cycle, but increasingly hard to come by. Biologists think this shortage may be a key factor in the crab's decline; in 2018, the crab was red-listed as "vulnerable" by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. To test the shell-shortage hypothesis, Laidre will embark on whole-island experiments under a four-year, $900,000 National Geographic Society grant.

The award will fund two graduate students and a postdoc native to the Indian Ocean region to assist with the fieldwork. Starting this summer, they will join Laidre in surveying 20 islands in the Indian Ocean to establish a baseline coconut crab population. At the end of the census, they will stock half of the islands with empty shells, and leave half untouched as an experimental control, to determine if increasing the housing supply will boost the crab's numbers.

In addition to testing their housing hypothesis, researchers will tag thousands of crabs with modern tracking devices to learn more about their movement patterns, life history and mating habits, and where females lay their eggs. They will inject RFID tags the size of a grain of rice into the crabs' abdomens to track them across their lives. They will also strap miniature GPS devices to the backs of adult crabs, and position cameras above their burrows to get a fuller picture of crab life. Another mystery Laidre hopes to solve is whether coconut crabs arrange coconut husks over their burrow as a signal to other crabs.

Laidre began his career studying land-based hermit crabs in Costa Rica, where he continues to do fieldwork. His focus expanded in 2016 when the BBC invited him on an expedition to film the coconut crab on a pristine chain of islands in the Indian Ocean. But by the time the permits arrived, the journalists had moved on. Laidre went anyway, and with funding from two prior National Geographic grants, he has studied the coconut crab up-close, gaining an appreciation for the unique challenges it faces.

The hatchlings spend several weeks at sea before paddling to land to search for an empty shell to call home. As the juveniles grow, they move into progressively larger quarters until their abdomens are calcified. They prefer the colorful spiral shells of marine Nerita snails, which they typically "remodel" to make roomier.

"The shell fits them better when it's at least partially remodeled," says Laidre. "This still gives them a grip to resist other crabs trying to pull them out and evict them for their shell."

Unfortunately for the coconut crab, and other terrestrial hermit crabs, collectors find Nerita shells appealing. On many islands, tourists often remove empty shells from the wild. The snails inside are also prized for their meat. For these reasons, shells are a scarce commodity, says Laidre.

Off-island, empty shells are plentiful and Laidre anticipates he will have no trouble rounding up the thousands of shells needed for the study. "Compared to the other logistical challenges of the experiments, it's almost the easiest part," he said. "Tens of thousands can fit into a large recycling bin."

The study will officially last four years, but because coconut crabs can live 50 years or longer, there's a chance that the tracking could outlast Laidre's lifetime.

"Long after this project, researchers can go back to the sites to see which individuals have grown and how a range of life-history events, as well as different conditions across the islands, have shaped each individual," he says. "Over those long decades, we can see the trajectory of their lives, which is super exciting."