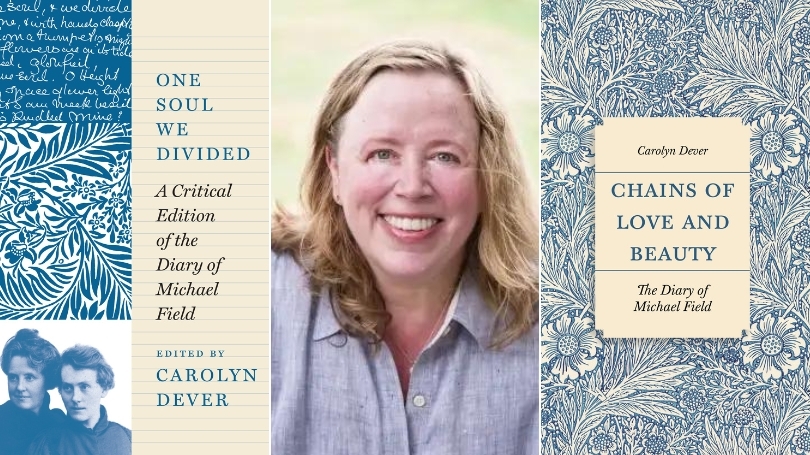

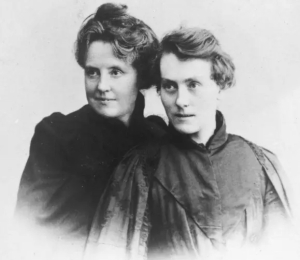

In two new books, professor Carolyn Dever champions the never-published diary of Michael Field, the pseudonym of 19th-century authors and romantic partners Katharine Bradley and Edith Cooper.

One day about 20 years ago, while on a walk through Nashville with a friend, Carolyn Dever mentioned her plans for a new book project: She wanted to write about Victorian domesticity—the ins and outs of daily home life in 19th- and early 20th-century England.

"It's a big topic and surprisingly complex—particularly when you consider it serves as a fig leaf to cover up ways of being and doing that can be quite counter to cultural norms," says Dever, noting she planned to focus on queer domesticity in particular.

Dever's friend told her she should look at Michael Field's diary.

"And that was the beginning and the end of the story," says Dever, a professor of English and creative writing. "It's been marinating for a long time—as it would need to. This archive is very significant.

Dever is referring to the 9,500-page, 29-volume unpublished diary co-written by late 19th-century British authors Katharine Bradley and her niece Edith Cooper, who went by the pseudonym "Michael Field." The two women were romantic as well as creative partners and collaboratively published eight books of poetry and 27 plays.

After immersing herself for nearly two decades in the study of the diary, which resides in the archives of the British Library, Dever has authored two pioneering scholarly books devoted to it, both published by Princeton University Press. The first, Chains of Love and Beauty, champions the diary as a great unknown "novel" of the 19th century and a work that bridges the Victorian marriage plots of George Eliot with the modernist experimentation of Virginia Woolf.

The second book, just published this month, offers the inaugural critical edition of the diary. One Soul We Divided: A Critical Edition of the Diary of Michael Field presents the first book-length selection from the joint diary.

In a Q&A, Dever discusses her fascination with Michael Field, how she winnowed the diary into a book-length format, her Dartmouth students' response to the text, and the revolutionary nature—or not—of its authors' lives and work.

What aspect of Michael Field's diary first caught your attention?

It's hard not to be grasped by their story. They're two women; they're writing as a man. They're aunt and niece; they're also a devotedly romantic couple. Their poetry is spectacular. They knew everybody: Reading these diaries is a "who's who" of late 19th century England, and Europe more broadly. So there's a kind of cosmopolitanism, a thoughtfulness, and an insight about art and culture and identity that comes out so clearly in these diaries.

You make the argument that the diary should be considered a great Victorian novel.

For many years I would describe it to people by saying, "In the right hands, someday it will make a great novel." Then finally, just a few years ago, I listened to myself say that again and thought, "Oh, maybe it already is." The diary has so many elements of the Victorian novel present within it. Presenting it as the great unknown Victorian novel is a thought experiment, a challenge to the field to think about what we do and don't count as a novel. This is a long, complex text focused on the lives of two women. It's busy with domestic details, pets, friends, frustrations, travel, and home decorating. It has subplots, structure, and narrative voice.

It shares many of the qualities of, say, Middlemarch, or Edith Cooper's personal favorite, Anna Karenina. Tolstoy's is a novel that Cooper explicitly admired because, as she said, "it contained everything." The diary, in its own way, also attempts to contain everything—not just the details of the outer world, but the details of the inner world; the details that are psychological.

How did you go about selecting what was going to go into this edition?

It was a painful process, because there's so much in here that's rich and necessary for the world to read. My principle of selection had to do with showing the deep and complex connections that Michael Field had with the world around them. For a long time they were seen as weird, or marginal, or just kind of irrelevant. But actually they were intense, smart, caring, and deeply engaged with one another and with the world of art and poetry in their time … That's the story of this edition. There are more stories to tell from it, as well, and someday we hope to have editions of the entire diary. Wouldn't that be amazing.

Together, Bradley and Cooper were "Michael Field," two women, one name. What was their collaboration like? Do their individual voices come through, or does Michael Field feature a new, blended voice?

There are many ways to think about voice in the diaries. One of those ways correlates with handwriting. In the manuscript of the diary, we can see quite plainly who wrote what, and we tend to think about that as voice. But then sometimes they're transcribing for each other, and sometimes they're copying a letter that the other one wrote, so the question of voice gets complicated even there.

As a person who's been writing about Michael Field for a while, it's not only the pronouns ("he" or "she" or "they") that are complicated, it's also the number. When we talk about Michael Field, we are talking about two people. I think that's the point for them—they're a poet. It's their job to get inside of language, to push language in different and unexpected ways, to challenge us and make us think differently.

Did they see themselves as revolutionary?

They were not revolutionaries. They were, from a political perspective, quite conservative. It wasn't actually all that unconventional for a pair of women who were related to one another, or even a pair of women who were friends with one another, to create a household together. It was called a "Boston marriage." There are many reasons behind this practice, including expedience, convenience, resource sharing, sexual identity, erotic identity, and companionship. The kind of intimacy we wouldn't blink an eye at if we're thinking about the Brontë sisters.

I think Michael Field presented themselves as an abstract ideal of poetry and poetic excellence. They weren't trying to overturn things; they were trying to write the most relevant, remarkable poetry of the time. And I think they understood that their gifts and talents would not gain them the recognition they deserved.They knew that would change someday, and they were absolutely correct in that, because here we are. But in their lifetimes? No.

Did Bradley and Cooper associate with other poets and writers at the time? And if so, was it intentional?

Yes. It was a small world. They visited gallery openings, talks, and musical events, and they knew everybody. They knew Oscar Wilde, William Butler Yeats. They knew Henry Havelock Ellis, the physician and essayist who invented the term "heterosexuality." They knew the painters Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon, a queer couple. They knew Vernon Lee, the pseudonym for feminist writer Violet Paget, John Ruskin, Rudyard Kipling. They visited the Paris Morgue and the Louvre, compared the theatrical performances of Sarah Bernhardt and Elizabeth Robins, snuck out of a dull performance of Tristan and Isolde after strong coffee at the interval did not do the trick. They looked on wistfully as Olive Schreiner reveled in worldly experiences they themselves missed.

You mention in your introduction to One Soul We Divided that you had your students read through your critical edition of Michael Field's diary and that they taught you a great deal in the process, both about the work and about how to teach it effectively. How so?

It's interesting to see what excites them about the work. For one thing, students are completely unfazed by the queerness of the work. They're really interested in the fact that these two women gave themselves a name, and constructed a life, and published canonical poetry, and decorated their home and had this weird dog and all this stuff. That resonates for them.

What they call the "incest plot" is really tricky for people to understand, but coming at the end of a course where we're talking about Victorian marriages and Victorian friendships, it's just one more model of marriage, and poetry and a dog are one more version of children. So they were really accepting, and intellectually engaged, and appropriately outraged at certain moments of obnoxious behavior by Michael Field or by others to Michael Field. It's so much fun. It's part of what makes me realize that this really is a book.

What do you think Michael Field would make of today's emphasis on pronouns?

I think they would not recognize themselves in today's debate for a whole bunch of reasons. The history of gender-neutral pronouns is peculiar. I remember when I was in college, those of us who were feminists on the campus undertook a campaign to insist that our university use accurate pronouns, because back in the day, everybody was referred to as "he." So Michael Field, in opting for "he," are actually being conventional. They're calling out that convention and pushing it to an extreme.

But also the name Michael Field—the reason it's not just an authorial pseudonym—stood for their marriage. Their marriage was a marriage of poetry, as well as love and domestic commitment. The poetry that they produced together in this erotic collaboration turns into the children that they didn't have, or that they did have by means of poetry.

Their comparison poets were Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, who were married to each other, but Michael Field said, "[T]hose two poets, man and wife, wrote alone; each wrote, but did not bless or quicken one another at their work; we are closer married." Whereas Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning had two poetic voices. Michael Field found a way to present the symbolic union of poetic voices as a form of marriage.