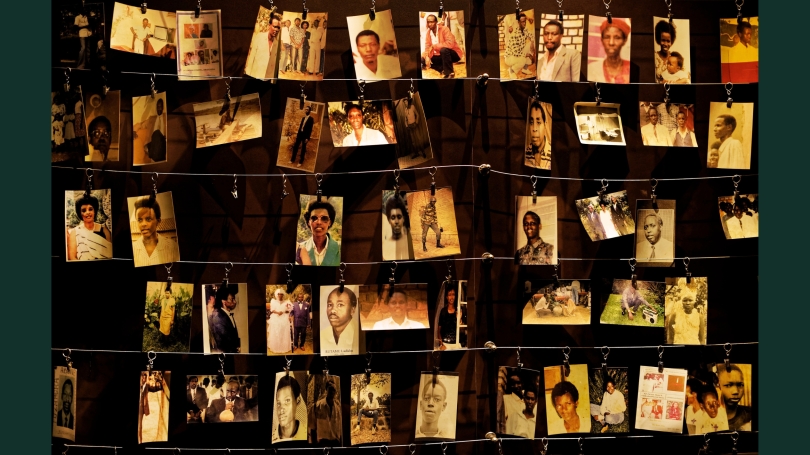

Trauma has lingering and multigenerational impacts. In 1994, more than a million people were killed in Rwanda during the genocide against the Tutsi, and it's estimated that between 250,000 and 500,000 women were raped.

A new study shows that prenatal exposure to this extreme violence altered the gene expression of children who were conceived during the 100-day genocide, particularly for individuals who were conceived through genocidal rape. However, these epigenetic patterns were also influenced by the individuals' early life experiences, suggesting that interventions could mitigate the biological impact of prenatal trauma. The findings were published this fall in Scientific Reports.

"Our findings highlight the multi-generational consequences of violence," says senior author Zaneta Thayer, an associate professor of anthropology. "Trauma doesn't necessarily end when the violence stops, but targeted interventions could mitigate these effects. And this research unfortunately remains relevant because we have continuous global conflict."

The paper is a follow-up to a 2021 study by Dartmouth researchers that showed that Rwandans who were exposed prenatally to the 1994 genocide have poorer physical and mental health compared to those conceived by Rwandan mothers who were not present during the genocide.

In the new study, the researchers investigated whether this prenatal trauma may have also impacted these individuals' "epigenomes"—chemical modifications such as DNA methylation that impact how genes are expressed (e.g., by turning a gene "on" or "off", or turning its expression "up" or "down").

Previous research on survivors of mass violence including the Holocaust, genocide against the Tutsu, and conflicts in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Kenya have shown that early life exposure to trauma is associated with DNA methylation of genes involved in the stress response, metabolism, and neurodevelopment. However, these studies did not examine different types of prenatal trauma such as rape, and did not consider the influence of subsequent adversity during early childhood.

"The experience of genocide is not isolated to the 'acute' experience," says Thayer. "If you experience this, and particularly if you're conceived through rape, there are lingering impacts across life in terms of the likelihood of exposure to stress and trauma."

The team examined DNA methylation patterns from drops of blood obtained from 91 24-year-olds who were conceived during the Rwandan genocide: 31 individuals conceived by genocidal rape, 30 individuals conceived by genocide survivors, and 30 individuals conceived by Rwandan mothers who were not in Rwanda during the genocide. They analyzed the three group's DNA methylation patterns in the context of data that they previously collected regarding the participants' adverse experiences in early childhood—for example, exposure to physical, sexual and emotional abuse or neglect.

Their results show that prenatal exposure to trauma can impact the epigenome, but that experiences during early life might be just as important.

"Prenatal exposure to genocide has long term biological effects, which the postnatal environment can either exacerbate or mitigate," says co-author Glorieuse Uwizeye, a Rwandan genocide survivor who initiated the project. Uwizeye was formerly a postdoctoral fellow of the Society of Fellows at Dartmouth and is now an assistant professor at Western University in Ontario, Canada.

Geisel School of Medicine Professor of Epidemiology Brock Christensen also served as a co-author of the paper.

Two genes had DNA methylation patterns that were associated with prenatal trauma exposure: BDNF, which codes for a protein that is involved in neuron growth and development, and SLC6A4, which codes for a serotonin receptor. These patterns were significant only for individuals who were born of genocidal rape but not for individuals exposed prenatally to genocide. Methylation of both BDNF and SLC6A4 was associated with more severe depression and anxiety symptoms.

When the researchers adjusted their analysis to account for the participants' adverse experiences during early life—for example, the degree to which they remember being exposed to physical, sexual and emotional abuse or neglect—only SLC6A4 remained statistically significant, suggesting that early life experiences can alter the biological impacts of prenatal trauma for some genes. The adjusted analysis also revealed a third gene, PRDM8, which is involved in neuron development, with altered DNA methylation patterns.

"What happens when a baby is gestating can have very big effects, and that means we need to be especially attentive to the needs of pregnant women who are living in humanitarian disasters," says first author Luisa Rivera, a Neukom postdoctoral fellow in anthropology. "So prenatal life matters, but childhood and early adolescence matter just as much—if that baby goes through life experiencing the stigma of everything that happened in the genocide, it can also affect their health in a long-lasting way."

The researchers are now initiating a more expansive cohort study that will focus on understanding how policy support, interpersonal support systems, and other environmental factors might buffer the adverse health impacts in this population.

"In this first study we collected data just once, but with the study we're planning, we hope to follow these individuals for many years to really understand the long-terms effects of the genocide on their lives, and the lives of their children as well," Uwizeye says.