- About

- Departments & Programs

- Faculty Resources

- Governance

- Diversity

- News

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

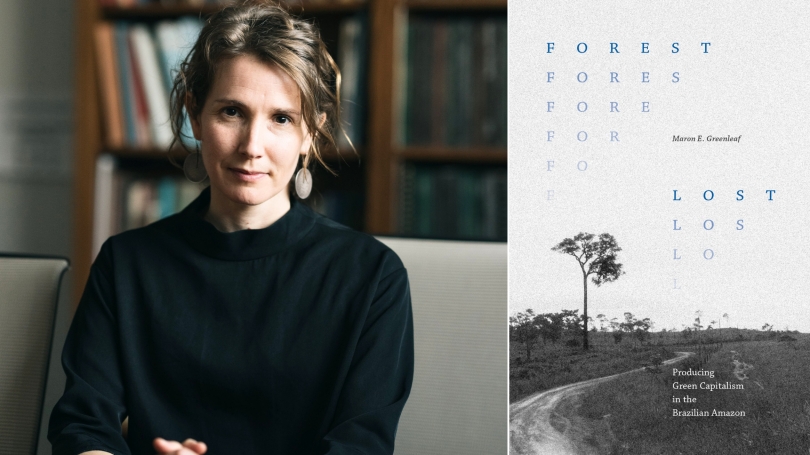

In her new book, Forest Lost, anthropology professor Maron Greenleaf explores how the market forces threatening rainforests worldwide can be marshaled to help protect them.

As a fix for climate change, carbon offsets (also known as carbon credits) have been both widely embraced and critiqued. By paying more for things like airplane tickets and heating oil, those of us in wealthier countries have a chance to 'offset' our carbon emissions, sometimes by paying people in poorer tropical countries to save their rainforests. The logic goes that preventing deforestation through payments can avert emissions and protect ecologies for forest species and people.

Carbon offsets are part of larger schemes to use markets to solve seemingly intractable problems like climate change and biodiversity loss—problems that markets themselves helped to create. This attempt to remake capitalism into something more socially and environmentally benign was gaining traction as Maron Greenleaf, now an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology, entered law school in 2007.

At the time, governments, businesses, and organizations worldwide were discussing how carbon markets might incentivize developing countries to save their rainforests. While finishing her law degree, Greenleaf decided she wanted to know more about how these emerging commodities would impact people on the ground.

She enrolled in Stanford's PhD program in anthropology and did extensive fieldwork in Brazil's Amazonian state of Acre. Her new book, Forest Lost: Producing Green Capitalism in the Brazilian Amazon, is based on her research in the Amazon. (This interview has been edited for clarity and length.)

What led you to write this book?

The Amazon is the world's largest rainforest. It's both a massive store of carbon and a massive source of carbon when it burns. It's also a place that many U.S. readers may be unfamiliar with, beyond tired tropes. I wanted to look at what impact our efforts to address climate change through carbon offsets and other financing mechanisms would have on people living there.

How do carbon offsets work?

They are meant to compensate for carbon emissions produced primarily by burning fossil fuels. They can be used to pay people in a place like Acre not to deforest, or to produce other things—crops, for example—in ways that protect the forest.

Did your fieldwork produce any unexpected insights?

I went to Acre thinking that I could study carbon offsets the way scholars have studied traditional commodities: following the supply chain through production, marketing, and sale. But I found I couldn't study forest carbon in this traditional way. I couldn't follow it. I couldn't find where a particular carbon offset was produced in Acre and track it to a buyer in, say, the U.S. This forced me to think about forest carbon differently: not as a thing I could follow but as a state of being—carbon kept in trees and soils instead of being released into the atmosphere.

Can a forest be treated as both a 'state of being' and a commodity?

I would argue that forest carbon can be. As commodities, forest carbon offsets are contingent on carbon's state of being: on it being held in place in forests. How do you keep carbon in place in forests? By making the living forest valuable. In many economies, forests are primarily valuable when you cut them for timber, or to make space for agriculture, roads, or buildings. Living forests don't have much economic value beyond ecotourism. Forests mostly become valuable when they're destroyed. The idea behind forest carbon offsets is that the living forest can be made valuable if we pay people to protect it or forgo cutting it.

But that's not so easy to do. A lot of what I studied in Acre involved trying to get rural people to produce forest products, like açaí berries, rubber, and farmed fish, in sustainable ways, without cutting or burning the forest. People in the Acrean government talked about this as 'valorizing' the living forest: making it monetarily and culturally valuable. The forest's valorization would keep forest carbon in place, allowing the state to access money via mechanisms like offset sales.

Brazil's interstate highway, BR 364, cuts through Acre. Why is it so central to your book?

Roads like the BR 364 are one of the main causes of deforestation in the Amazon. But the BR 364 was also important to bring into the book because many rural people experienced it as such a positive part of their lives. It let them access schools and medical care, to buy consumer goods and sell products they grew and collected. In the U.S., we might want to pay to keep the Amazon "pristine," but for many people living there, roads are not just harbingers of deforestation, they also make life livable.

Also, the Acrean effort to valorize the forest relied in part on producing more products sustainably and most of those products had to be transported via the BR364. So the road both threatened the forest and offered a way to protect it. In this way, I use it to explore the tensions and contradictions of "green capitalism": trying to use systems that have caused environmental degradation to now protect the environment.

Why do carbon offset critics see them as a modern form of colonialism?

There are several types of arguments. One is that we in the Global North, who have deforested a lot of our land to "develop," are now paying people in the Global South to maintain their forests in ways that will keep them poor, reproducing a colonial relationship. I heard this frequently in Brazil both from more rightwing politicians and from normal people I met.

There's another set of arguments that see carbon offsets as part of the historical and ongoing extraction of natural resources from colonized places. This extraction has largely enriched people elsewhere because the value of extracted resources typically accrues to the places where value-added products are produced and consumed. Carbon offsets can seem like another commodity that reinforces this dynamic: they pay little to people in forests and allow continued accumulation in wealthy places through enabling the ongoing burning of fossil fuels.

Moreover, many think that carbon offsets don't work—that they don't actually help reduce greenhouse gas emissions. And because climate change itself is so unequally experienced, offsets reinforce global inequality.

Based on your fieldwork, do you think carbon offsets can work?

I don't categorically reject them as some critics do in part because I think they're here to stay. But it's tricky when we value timber, and the soy and cattle that replace the rainforest, so much more than sequestered carbon. Some people in Acre I know have found it very difficult to make the living forest itself valuable. They worked hard to create carbon offsets and otherwise access funding for emissions reductions, but much of the expected funding never materialized.

Promises of forest carbon-linked money did, however, raise expectations in Acre, and create disillusionment with the government. For example, in 2018 and 2022, large majorities of Acreans voted for rightwing populist presidential candidate Jair Bolsonaro, who campaigned on and governed in ways that undermined forest protection. This was a huge political change for a state that had voted for leftwing environmental candidates in the past. I found a widespread sense in Acre that forest protection had benefited people in the cities more than in the countryside and fueled growing inequality. In Acre, you can see how green capitalism raised expectations, and when those expectations weren't met, how it contributed to the rise of right-wing populism and deforestation.

Do you think green capitalism can live up to its promise?

It's such a tricky question. I don't think green capitalism is going to save us. Capitalism creates and reinforces inequality, and it creates and reinforces environmental degradation. That's part of how it works. But there are meaningful ways to make markets fairer and less environmentally destructive. Social change is inevitable, but it usually doesn't unfold as planned. This means that what green capitalism is, and what it may spawn, isn't predetermined. We can't afford to disengage.

In my mind, this applies to offsets too. Where offsets are harmful, that's a problem; where they're allowing us to continue to burn fossil fuels, that is also a problem. But where they are helping to protect forests in a just way, and facilitating the transition from fossil fuels, there's a role for them.