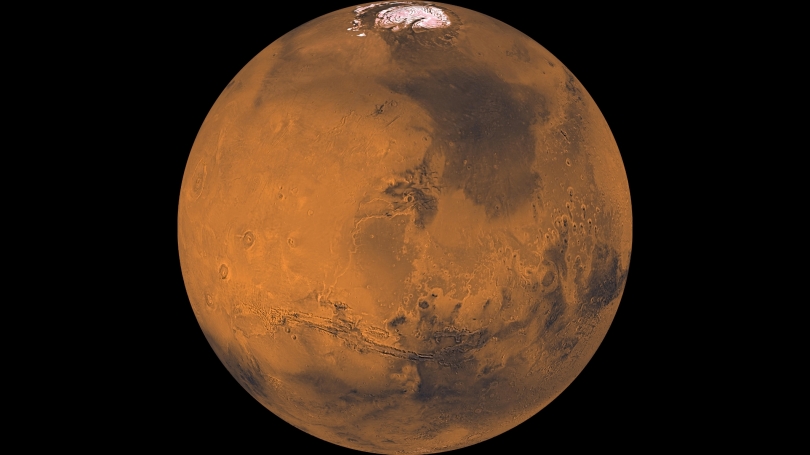

Research by Earth sciences PhD student Katherine Lutz and professors Marisa Palucis and Robert Hawley illuminates ancient water sources on the Red Planet.

As a first-year master's student in the Department of Earth Sciences, Katherine Lutz became fascinated by satellite images of Mars that showed spiraling shapes swirling across the planet's polar ice caps.

Consisting of alternating layers of ice and dusty deposits and measuring 400 to 1,000 meters deep, these spiral patterns aren't seen anywhere on Earth.

"These look amazing, but do we actually understand why they form or how they evolve over time?" asks Lutz, now a Guarini School of Graduate and Advanced Studies PhD student and National Science Foundation Fellow in the lab of professor Marisa Palucis, whose research areas include planetary landscape evolution. "Why are they here? How can we use these features?"

The layers on the polar ice cap offer scientists one of the best climate records for the Red Planet.

"Mars has undergone massive climate change and we spend a lot of time as planetary scientists trying to understand that," Palucis says. "The question of how much water has flowed across its surface (and when) has been central to its exploration."

Research from 2013 had suggested these "troughs" might be caused by katabatic winds—winds that start off moving rapidly, causing erosion, and then quickly drop and slow down, resulting in deposits. As a result, the troughs would be expected to have asymmetric walls as well as cloud formations hovering over them that correspond with katabatic wind activity.

With Palucis and Earth sciences professor Robert Hawley, Lutz analyzed a decade's worth of new Mars images and data and discovered that while 80% of the troughs were indeed asymmetric, roughly 20% were not. Rather, the troughs on the outer edges of the ice cap form a fairly uniform "V" shape, with the walls on either side measuring about the same height. Further, not all troughs had cloud cover.

In a paper published this year in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, the researchers posit that these outer troughs are younger than those in the center of the polar ice cap and are likely caused by heavy erosion versus a katabatic wind cycle. That could suggest, Lutz says, that 4 to 5 million years ago, there was a shift in the Martian climate that altered the planet's water cycle, causing winds, clouds, and ice to flow differently.

This would help explain why the troughs in the center of the ice cap are different from the ones on the edges, Lutz says: they formed at different times, under different climate conditions.

This type of discovery is crucial in trying to decipher whether Mars can support—or has ever supported—life.

"If we ever want to have people on Mars, we need to figure out the history of this water source," says Lutz, referring to the ice layers in these spirals. "Could we potentially be using it to, say, extract drinkable water? And if we ever want to find evidence of life there now, we're not going to look at the outer edges of the ice cap, where it's just a lot of erosion and no water going into the system and there's not a lot of heating."

Lutz is quick to point out that these ice-cap layers are only records of climate on modern Mars. More modeling is needed to further illuminate the history and function of these unique spiral features, with the eventual goal of sending a physical rover to Mars to "get some more concrete information" about the troughs.