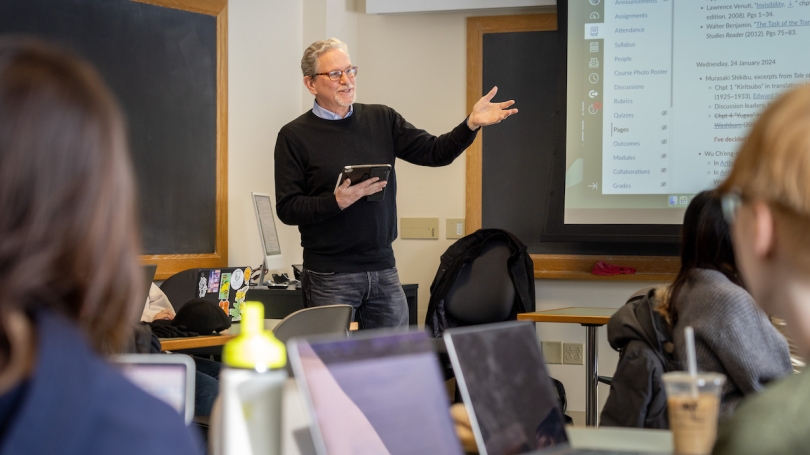

Professor James Dorsey's research probes the intersection of culture and politics—and fosters a creative approach to translation.

Students in professor James Dorsey's winter 2024 course Translating East Asian Languages: Theory and Practice may have been be surprised to find a few American names on the syllabus: Bob Dylan, Pete Seeger, and Woody Guthrie.

The material for this section of the course—which explores how Japanese singers translated and adapted songs by American folk icons—is derived from Dorsey's research on the Japanese folk song movement of the 1960s.

"A lot of the earliest Japanese folk songs were translations or adaptations of American songs," says Dorsey, an associate professor in the Department of Asian Societies, Cultures, and Languages.

"There was a clear creative input in the act of translation, but it was also very clear that these ideas and expressions had come out of a worldwide community. Singing a Japanese anti-war song based on an American anti-war song connected artists and audiences to a global community of the same spirit. People celebrated that," Dorsey says.

A translator, researcher, and literary scholar, Dorsey has dedicated his academic career to probing the interface of culture, ideology, and power.

"The Japanese folk song movement was a point where culture intersected with politics—which is an intersection I'm always drawn to," Dorsey says. "From the moment I discovered it, I was off to the races."

Pursuing a Passion

Dorsey first encountered Japanese folk songs while seeking material that would help students in Dartmouth's Japanese Language Study Abroad program enhance and enliven their studies of the Japanese language. The songs fit his criteria: Written by native Japanese speakers, yet accessible enough for intermediate-level Japanese language learners.

"The folk songs use a very simple, everyday vocabulary, but have a political or ideological angle that can lead to interesting discussions," Dorsey says. "I thought, 'This stuff is great.'"

Dorsey, who also teaches a Japanese martial arts class as a "great window" into Japanese culture and traditions, has now spent more than a decade studying the politics, artists, songs, and influence of the 1960s Japanese folk song movement. He has published articles on the topic in academic journals in both the United States and Japan, and is currently working on a full-length book. He also shares songs from the movement on his YouTube channel and presents lectures around the world.

Dorsey recently spoke on the subject of "kaeuta"—a defining characteristic of the movement—at a conference in Estonia via Zoom.

"Kaeuta is the practice of taking a familiar melody and plugging in your own lyrics—whatever makes sense to you," Dorsey explains. "Kaeuta was widespread in Japan in the 1960s; people advocated for its use because it lowered the bar to participation in the folk song movement. It's not easy to come up with a melody on your own. But if you take a few minutes, you can easily come up with lyrics to a popular tune, have some fun with it, and say something meaningful," he says.

"It's really fun to see how the message of these songs would evolve with each new set of lyrics. Sometimes the themes would be very similar. Sometimes they would be the very opposite."

Through his research, Dorsey has connected with one of the movement's most popular artists, Goro Nakagawa. The two met when Dorsey began attending the singer's concerts in Tokyo.

"I would grab him after the performances and ask to speak with him," Dorsey says. "Once, I asked him to sign a copy of the book he wrote; he thought it was hilarious that some American scholar was a fan of his work."

Since their first meeting, Nakagawa and Dorsey have developed a symbiotic professional relationship.

"I occasionally email him questions about the movement if I'm unsure about something," Dorsey says. "He's also a translator, and he sometimes asks me questions about translations he's working on. A few years ago, he asked me to create English subtitles for a protest song he wanted to post online."

Nakagawa has also made guest appearances in Dorsey's classes via Zoom—despite the 14-hour time difference between Tokyo and Hanover.

"He's always happy to speak to my class, even though it means he's Zooming into a 10 a.m. class at 11 o'clock at night," Dorsey says. "One of the students always ends the session by asking him to perform for us, and he always gladly obliges. My dream is to someday invite him to spend some time on the Dartmouth campus and lead a couple of sing-alongs and a talk about his work with translation."

Teaching Translation Through Song

Beyond the LSA+ program, Dorsey utilizes his research in several of his on-campus courses. Japanese folk songs have become a key component of Dorsey's translation courses, offering students a chance to engage in cultural analysis while practicing a more advanced approach to translation.

"The tendency when we translate is to look for one-to-one word equivalencies and follow mechanical grammatical formulas to transpose from Japanese to English," Dorsey says. "You can do that with prose and produce something that sounds kind of like English, but when it comes to song lyrics, you have to be more flexible and creative."

Dorsey challenges his students' skill and creativity by asking them to complete two versions of the chosen song.

"The first is a poetic translation, which is meant to capture the meaning and the spirit of the original lyrics," Dorsey says. "The second is a version that can be sung to the same melody. This creates another set of complications, which helps us polish our abilities to write in English."

Through the second translation, students follow in the footsteps of the artists Dorsey studies.

"It's an interesting project, because it's exactly what the Japanese folk singers of the 1960s were doing: Translating the songs they heard, having people try to sing them, and then polishing them," Dorsey says. "It's a fascinating collaborative effort."

Dorsey's research takes an even more prominent role in his course Social Revolutions East and West: Japan and America in the 1960s.

"Japan was very politically volatile in the 1960s," he explains. "It was very much like the United States in the same period, with student movements, anti-war demonstrations, and protests on college campuses."

The folk song movement was a vibrant subculture of these ideological revolutions. By studying the movement, students gain historical perspective on some of the forces that continue to shape Japan's politics, art, and culture.

"The progressive liberal movements that are at work in Japan today have their roots in the 1960s," Dorsey says. "One particular example of this is the terrible earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear disaster that struck Japan in 2011. Because of what happened at the Fukushima nuclear plant, the anti-nuclear movement spiked again."

With the return of the anti-nuclear movement, kaeuta also reappeared, giving new life to a popular 1960s tune.

"A song called Let's Join the Tokyo Electric Company made its way around Japan after the disaster," Dorsey says. "It's a satirical kaeuta that mocks the company that owned the Fukushima plant by putting new lyrics to a melody that was made popular in the 1960s as a song called Let's Join the Self-Defense Forces."

The movement also introduced the concept of indie music to Japan as folk artists—censured by the recording industry—sought alternate methods of sharing their songs.

"The way folk songs were created, distributed, and enjoyed in the 1960s blew apart the conventional practices of the record industry," Dorsey says. "Rather than orchestrating popular songs in a top-down fashion, record companies began to discover and recruit people emerging from the grassroots. Japanese folk music opened the door for music to come out of places other than the established record companies."

Amplifying a Vibrant Japanese Voice

Dorsey's latest project unites his work as a translator with his passion for literature and his interest in 1960s-era Japan: an English translation of Shoji Kaoru's 1969 novel Be Careful Little Red Robin Hood.

"I love it because the voice of the narrator is unlike anything I have ever read in Japanese literature," Dorsey says. "It's very colloquial—it's sort of stream-of-consciousness—and it jumps around chronologically a lot."

The novel, which is said to be inspired by the Japanese translation of The Catcher in the Rye, follows a high school student whose life is upended by the student protests at Japan's top university.

"The protagonist has always wanted to go to the University of Tokyo, and he's organized his whole life around that goal," Dorsey explains. "However, the student demonstrations at the University of Tokyo are so violent that the administration decides not to accept an incoming class. It's like the rug got pulled out from under him; the news launches him into two days of soul-searching and agonizing over who he is and what he's supposed to do."

For Dorsey, creating an English translation of the novel is an opportunity to showcase—and refine—his skills as a translator.

"The challenge and the glory of the novel is the voice: playful, slangy, and full of digressions," Dorsey says. "Translating it well requires a mastery of English and Japanese that's different and greater than the language ability needed to translate a more plot-driven novel."

Dorsey met the author in Tokyo in December and he graciously granted permission for the English translation to be published.

"Shoji, who is now in his 80s, is quite keen to see the book come out in English," Dorsey says. "I'm very excited about it. It's really, really fun."