Amy Schiller, a visiting scholar and former postdoc in the Society of Fellows, argues in her debut book that contemporary philanthropy must transcend its focus on basic human survival.

Growing up in Cleveland, Amy Schiller was surrounded by majestic civic institutions such as the Cleveland Museum of Art, which was built during the Gilded Age for the enjoyment of everyone.

She was especially struck by the museum's motto: "For the benefit of all the people forever."

"That's something that only philanthropy can do—think in that capacious and unbounded way about the benefits that money can produce," says Schiller, a visiting scholar and former postdoc in Dartmouth's Society of Fellows.

As a fundraising consultant in New York City following her graduation from college, Schiller observed how philanthropic institutions, in general, tend to focus on less lofty goals.

"I noticed people starting to use a different vocabulary around their goals for giving," she says. "That got me really interested and is part of the reason why I went to graduate school: to study philanthropy from a more scholarly and theoretical perspective."

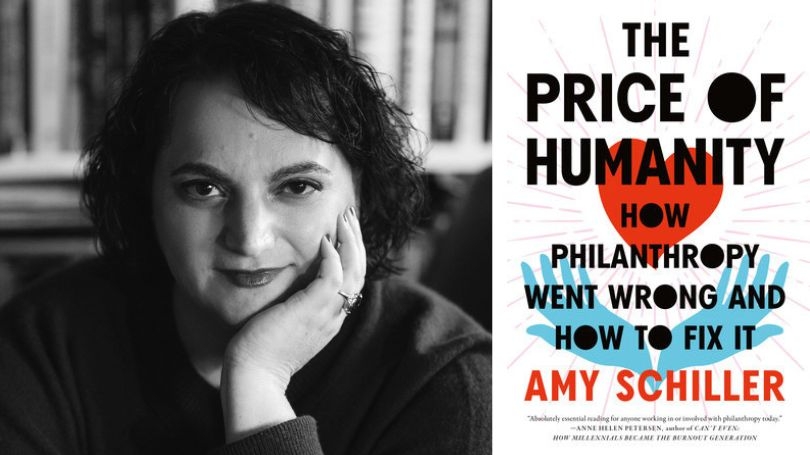

Her debut book, The Price of Humanity: How Philanthropy Went Wrong and How to Fix It, chronicles contemporary philanthropy's evolution and champions a return to its original impulse: to support the flourishing of humanity—the creative, intellectual, philosophical, and other endeavors unique to humankind.

In a Q&A, Schiller elaborates on her critique of contemporary philanthropy, why she believes the act of giving should be accessible to everyone, and how the Dartmouth community proved instrumental to writing the book.

What motivates you to study the politics of wealth and philanthropy?

Philanthropy contains a lot of really important social and cultural negotiation. My shortest way of describing this is that philanthropy literally means "love of humanity," which means that when we talk about giving as a society, we are also generating definitions of humanity. We're understanding what it is that we value. What kinds of human life are we deeming worthy of our support?

When I tell people I write about philanthropy, their eyes light up. People have a lot of thoughts and opinions. They'll ask, "Oh, are you going to write about tax breaks ?" "Oh, are you going to write about Jeff Bezos going to space?" There are a lot of associations that people have in their minds with this topic, but there aren't very many invitations to discuss them directly. And that's what excites me about studying philanthropy—I can offer a framework for having those conversations and for surfacing the negotiations that are already happening within philanthropy discourse that often go unnamed.

You argue that philanthropy should not target basic human survival, which instead should be the goal of government and other public institutions. Rather, philanthropy should focus on allowing people to flourish into more fulfilled human beings. Why is it problematic for philanthropic giving to focus on alleviating poverty?

In early Christianity—and St. Augustine is the figure that exemplifies this—we have this sharp turn from basic survival needs towards giving in a targeted way to the poor. And in many ways that sounds good, because we think we want our giving to go where it's most needed, where people need it to actually survive. But the book details the problems with defining philanthropic giving in that way. It leads us to objectify poor people, to sort of instrumentalize them for our own feelings of virtue or our own feelings of efficacy. It transforms things that should be provided as a right into things that are provided by richer people's discretion.

I argue that it's actually worse when our basic needs are met through charitable giving and not through democratically governed institutions and a robust social welfare state. There are two key phrases in the book that summarize this. The first, which is a riff on a political slogan used during the women's suffrage movement, is: "Government for bread, philanthropy for roses."

In other words, we don't just want the bare necessities of life; we want culture, we want education. We want things that truly make life worth living. And I find it very meaningful that philanthropy can actually provide those. It's not subject to the same demands of the market to use money in a cost-efficient way to generate a defined return on investment. You can say, "We're going to create something that is simply a value to everyone."

The second phrase that I use to underscore this point is "magnificent philanthropy." That's about embracing the value in creating beauty and connection, which doesn't even have to be on a grand scale. Creating the spaces and institutions that offer that to as many people as possible is the goal.

In a recent op-ed in the Daily Beast, you examine, through the case study of Mackenzie Scott, how today we have billionaires donating money to tackle issues like poverty and sanitation. Does this epitomize today's definition of philanthropy?

At this point, inequality and concentrated power is the norm. Philanthropy is symptomatic of that. It's symptomatic of those larger forces in our political economy.

I'm adding one more argument for greater economic justice—I feel that it's important to provide a vision of what we are striving for. It's a counterintuitive argument. We need to have more justice for workers and for marginalized people, and we need a more robust social welfare state to provide everyone the means to live a dignified life. And my way of contributing to that is to say, among all the other reasons to do so is the fact that it then frees up a lot of money to provide things that we need to help us flourish.

Ultimately, when the billionaire class controls philanthropy, we're reduced to our basic needs as human bodies. It really is important to keep our eyes trained on what more we are, and what more we can be. There are examples in the book that show that it is possible in this transitional time to do both—meet both basic and loftier human needs—and that, in fact, we need to do both.

What are some examples in the book of philanthropic giving that accomplishes this dual purpose?

The book is structured around three pairs of major figures of philanthropy, each pair including one historical figure and one contemporary figure. The final pair is Jane Addams, founder of Hull House in Chicago and a pioneer of the settlement house movement, and LeBron James, a household name for his legendary basketball career.

Jane Adams founded Hull House in the late 19th century in Chicago, and her vision was that working people who lived in the slums needed a space for gathering and recreation. She saw the danger of industrial capitalism to grind people down. She created this facility that provided many vital social services, such as relief loans and bath houses—9,000 baths were given in just the month of July one year—but the overarching purpose was to provide those needs in a setting where people were welcomed as full human beings who could contribute to the intellectual and cultural life of their community.

The contemporary example is the I Promise School for third- through eighth-graders in Akron, Ohio. It is a public school with an extensive support program funded by the Lebron James Family Foundation. Every student, for example, receives a bike and a helmet. LeBron described how having a bike as a kid is what made him feel free. He's clearly invested in these kids as full human beings, not just looking at whether their test scores are increasing, or whether they're going to be economically mobile. He wants them to have the means of joy and recreation and freedom.

It's very important that we understand that the ultimate goal is supporting people as full human beings, not just reducing them to their basic needs.

In a recent op-ed in the Los Angeles Times, you argue for a "giving wage" that "affirms true dignity" for all workers by enabling them to participate in philanthropic giving. How do you address the problem of who gets to be a philanthropist, and why is it important for everyone to take part?

A more democratized philanthropy would give people the means—via their wages and tax incentives—to participate. Right now, a charitable tax deduction only kicks in if you give more than the standard deduction. That means if you're a household with two adults, you have to have given away $25,000 or more in a year. That's a huge sum of money. The only people who are now getting rewarded with a tax deduction are people who can afford to give away a lot of money. I'm suggesting that we reverse that and make it a flat tax credit, so that it's geared more towards incentivizing participation than incentivizing the scale of giving.

We need to go beyond a living wage and offer a "giving wage" to enable everyone to participate in philanthropy. In the book, I tell the story of the crowdfunding of the Statue of Liberty. France gifted us the statue, but it was the United States' responsibility to figure out financing its installation. And this became a stalemate where Congress didn't want to pay for it and New York didn't want to pay for it. So the statue sat in a warehouse, like our unopened online shopping packages, for nine years.

Joseph Pulitzer, the politician and newspaper publisher of Pulitzer Prize fame, heard about this and started a campaign in The New York World. His exhortation to his readers was, We must raise the money. The statue is not a gift from the millionaires of France to the millionaires of America, but a gift from the people of France to the people of America. And his mainly working-class readership raised over $100,000, which is about $3 million in today's dollars, to cover the cost of the pedestal and installation of the Statue of Liberty.

That sense of personal investment, the ability to be part of something bigger than ourselves, really resonated. And these were people who were working for very meager wages at the time in a very unequal economy. Even under those circumstances, people wanted to help build the world that they live in.

You mention that your time at Dartmouth was instrumental to writing the book.

Dartmouth was a fantastic environment in which to write this book for a couple of reasons. One, the Society of Fellows postdoc was a terrific resource for anyone fortunate enough to have the opportunity. I made contacts and friends who read chapters, gave me great advice, and workshopped things across a ton of disciplines.

This also speaks to the book's broad appeal: It isn't just a narrow, disciplinary text. It contains art history and economics and sociology, and getting input from people from so many fields really enriched it.

Finally, teaching Dartmouth undergrads was so rewarding, and I got to have a lot of discussions that directly fed into the writing of this book. I cited several Dartmouth students in the book. I think the world of the Dartmouth community, and I'm glad to remain a part of it.