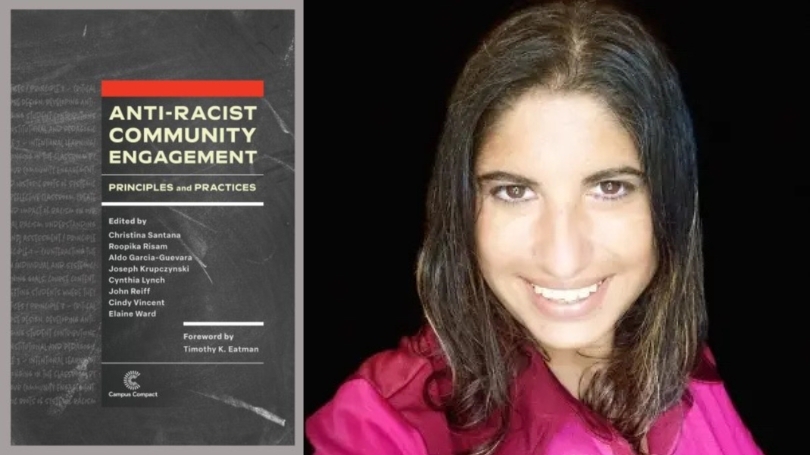

Professor Roopika Risam co-edited a new volume that brings anti-racist community engagement practices to a broad audience.

When researchers collaborate with community members and organizations outside of academia, how can they build trust? What are strategies for working collaboratively?

A new volume co-edited by professor Roopika Risam addresses this challenge and examines how decades of institutional and pedagogical practices in America's colleges and universities have thwarted opportunities for genuine collaboration and positive change within the communities they aim to serve.

Anti-Racist Community Engagement: Principles and Practices showcases community-engagement traditions that BIPOC academics and community members pioneered over the past century—a legacy, Risam says, that is often overlooked.

As associate professor of Film and Media Studies and of Comparative Literature, Risam joined the Dartmouth faculty last year as part of the Digital Humanities and Social Engagement cluster. Her research examines how digital methods can bring untold stories about Black, brown, and Indigenous communities to new audiences. Among her current projects, a new book under contract with Johns Hopkins University Press will recover the leading roles that African diaspora, Latinx, Indigenous, and Asian American scholars have played in the emergence of public humanities.

In a Q&A, Risam discusses the problematic history of academic engagement with communities of color, and how this new volume shows how to swap top-down "instruction" with ideals and methods that emerge from communities themselves.

How did this book come about?

When I was at Salem State University in Massachusetts, we had several grants to work on projects related to equity in community-engaged research. One of the grants led to the creation of the New England Equity and Engagement Consortium, a partnership of representatives from public and private colleges and universities in New England. We facilitate working groups on projects intended to improve DEI in community-engaged research and teaching.

Based on that research, with our students we created a series of principles which we took to focus groups of community partners; we then took their feedback and further refined these principles. Our consortium, in collaboration with Campus Compact, has run several popular symposia on community-engaged research. We brought in speakers who do this work and represent the values embedded in these principles.

With the support of Campus Compact, we decided to develop an edited collection to really showcase other people's voices. We wanted to shed light on different kinds of practices that foreground relationship-building with communities. The community's assets and needs are foremost—not the university's.

There is an emphasis for readers on "cultural humility" and decentering white supremacy. How does this work in academic and nonacademic settings, and what are the differences between the two worlds?

For the most part, predominantly white institutions tend to have a baked-in preference for white American and inherited-from-the-Enlightenment ways of doing research. There's also an assumption that the person in the university is the expert. In many ways, there is a certain amount of expertise that comes with having dedicated your life to a particular research area. But that isn't the be-all-and-end-all of expertise on a topic. There are different kinds of expertise. For example, there's expertise that comes from lived experience.

What's historically happened in community-engaged research and teaching is that the academic researcher goes into the community and says, "I'm here to solve your problems, and I've brought my students." It's a problematic dynamic because the researcher may not know anything about the context of the community, including its assets and needs. And the students have no knowledge or understanding of that either.

Community groups who are typically targets of university outreach have gotten wary of researchers. Often they drop in and extract the community's data and an experience for their students. Maybe they publish or get a grant and they benefit from it, and communities are left wondering, did that actually benefit us? That's the dynamic that we're interested in changing. The first question is about what expertise, knowledge, assets, and needs are in the community, and then, can we help? Not even, we're here to help, but can we? Is there something we should do?

For example, I had grant funding from Mass Humanities to teach digital humanities to high school students. Our proposed plans fell through, so I approached a school in Salem and asked whether the funds and idea would be useful to their students. They were looking for an experimental project to engage a group of seniors who were in danger of flunking out. We ended up creating a digital exhibit on Salem, all the students graduated, and some of them even continued on at Salem State for college. But I was only able to do this work because I had built up five years of relationships, and local partners knew me and they trusted me. We worked with a teacher to understand what she and the students needed and were interested in, and we built this project together. This is how we de-center the university as the locus of knowledge.

Some colleges and universities find themselves in new territory as they evaluate their historic records with regard to the land on which they are situated, their art and ethnographic collections, and generations of institutional racism. How do institutions of higher learning grapple with these complex issues?

I'm a co-principal investigator of a grant called Landback Universities, which explores this issue. It's not enough to think about the actual land parcels and financial benefits; there are economic, cultural, and community impacts. Focusing solely on real estate or dollars is a missed opportunity to think about different forms of repair that are more expansive, such as scholarship programs for Native students; dedicated spaces for Indigenous student groups to gather and participate in ceremonies; or what it might mean to have university lands, like an arboretum, put under the stewardship of an Indigenous community.

These initiatives happen because there are people who do the work. It may not be in their job description, but individuals are on the ground insisting that institutions address their histories. For example, the Hood Museum and the Dartmouth Library have been examining the provenance of their collections, asking who are the communities that have relationships to these materials, and what is our responsibility as an institution?

It is often the work of individuals with local relationships who get these projects started. It really takes people who care about these issues, who push and push. And then it has the potential to become a broader, institutionally sanctioned initiative.

What do you hope readers take away from this book?

As we were editing, we were thinking about how to distill replicable practices that other people could use. We really see that it starts with the input of communities being part of any kind of work from day one. It's figuring out if there's even a project and knowing as a researcher that people might say "No thank you," and that this is an absolutely appropriate response. Nobody owes you collaboration.

What I also think is really exciting about the book is that there are teams of authors who talk about missteps. Sometimes even people with the best of intentions can replicate the dynamic where academics crowd out community voices. But what's important is seeing the problems and being able to adjust and change your practices.

This book has a broad audience: community partners and academics, but also librarians, administrators, faculty, and students. We're in the process of putting together a digital companion, which will offer additional materials in an accessible format, including syllabi, agendas, handouts, and worksheets.

In addition to your work with Landback Universities, you recently helped create a permanent exhibit at Wellspring House, a nonprofit homelessness prevention organization, about a prominent Black family that was an early owner of the historic home in Gloucester, Mass. What inspires your own community engagement work?

The questions that drive me are: What does it mean to put our time and effort where our mouths are, in terms of caring about social justice? How do we actually take advantage of what we have in universities to support the communities around us and to improve those relationships?

There's often a sense in the scholarship that this kind of community engagement dates to the 1990s. But when you actually look at the initiatives and the programs built by Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and Asian scholars from the minute they got to universities 100 years ago, you see that this has a long history. And the people who built fields like ethnic studies weren't doing this work and getting a pat on the back. People were saying, that's not legitimate work. Why are you doing this?

For me, much of wanting to help shift the conversation toward more equitable and anti-racist and anti-colonial ways of doing community-engaged work is in recognition of the people who've been doing this for over a century in meaningful and real ways