- About

- Departments & Programs

- Faculty Resources

- Governance

- Diversity

- News

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

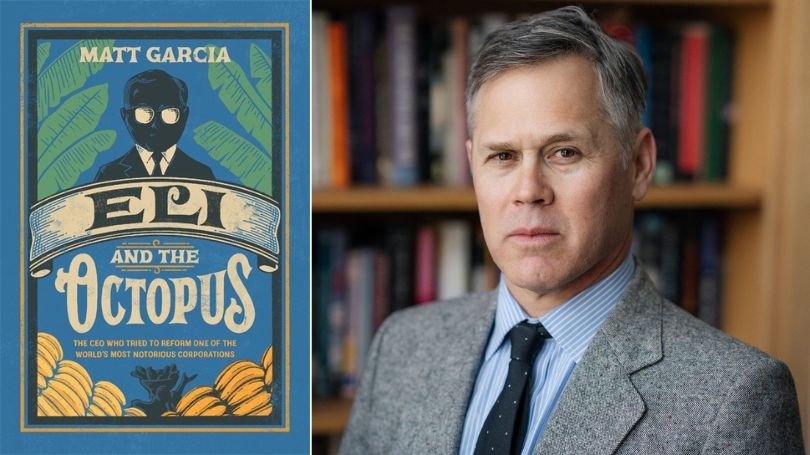

In his new book published by Harvard University Press, Eli and the Octopus: The CEO Who Tried to Reform One of the World's Most Notorious Corporations, professor Matt Garcia chronicles the tragic quest of an idealistic immigrant to improve the world through a multinational corporation.

In June of 1970, about four months before the economist Milton Friedman famously argued that a company's sole obligation to society is to make money, rabbi-turned-businessman Eli Black took the helm of a multinational agricultural company with hopes to improve the world.

"Socially conscious programs, designed to improve the quality of living of employees, are indeed the legitimate concern of business," Black wrote soon after he merged his own company with United Fruit, a business whose dark legacy had earned it the name of "el pulpo"—the octopus—for its sprawling efforts in Latin America to benefit its American shareholders.

Less than five years later, Black died by suicide. News reports shortly thereafter said Black played a role in bribing the president of Honduras to lower taxes on United Fruit bananas.

With Eli and the Octopus: The CEO Who Tried to Reform One of the World's Most Notorious Corporations, his new book published by Harvard University Press, Professor Matt Garcia offers Black's story as a parable for our times. Named among Bloomberg's best new books of spring, the book narrates Black's life and the trajectory of his conglomerate, United Brands, in a page-turner style, from his voyage by boat at age 4 from Lublin, Poland, to New York City, to his unlikely friendship with labor rights activist César Chavez.

The book represents Garcia's third scholarly examination of food worker exploitation in the agricultural industry. His first book, A World of Its Own: Race, Labor, and Citrus in the Making of Greater Los Angeles, 1900-1970, investigated the influence of Mexican and Asian laborers on the citrus-growing regions of eastern Los Angeles. In his 2012 book, From the Jaws of Victory: The Triumph and Tragedy of Cesar Chavez and the Farm Worker Movement, Garcia shifted his perspective to organizers by illuminating Chavez's celebrated accomplishments and lesser-known shortcomings.

Garcia joined the Dartmouth faculty in 2017 and serves as the Ralph and Richard Lazarus Professor of History, Latin American, Latino, and Caribbean Studies, and Human Relations.

In a Q&A, Garcia discusses the inspiration behind Eli and the Octopus, why he insisted on referring to Black on a first-name basis, and what business leaders can learn from Black's story.

You're a business owner yourself of a small farm in Thetford, Vt., which offers grass-fed meat and a goal of repairing the environment. Was your experience merging business with social responsibility part of the inspiration for this new book, which in some ways traces the origins of the "doing well by doing good" movement?

I come from working people. My grandmother worked in agriculture. She traveled up and down California picking crops, and she worked at Claremont College feeding students. My father owned a meat market in Southern California, and I cut and sold meat. I continue this line of work today with the farm that I own in Vermont.

Watching my dad operate his business, and running my own farm, I understand that it's very hard to maintain a business. (I think sometimes we academics give that short shrift; we work in a context where we don't really think about how things get made and sold, or the pressures of managing a business.) I wanted to tell a story that appreciates the leadership challenge of creating and running a business, while not abandoning the voices of workers—what historians sometimes refer to as "bottom-up" perspectives—and how laborers contribute to a company's overall value.

Tracing corporate social responsibility back to the 1970s, an era when Milton Friedman advocated that businesses should do nothing but increase profits for shareholders, is not an automatic thing to do; I'm taking it there because Eli Black's story has resonance for our times. He charted a completely different course for his company, tilting against the wisdom of someone we've all come to venerate. In many ways, Eli conveyed that business should be a partnership between the management and the people who are actually doing the work.

With its narrative-driven structure, Eli and the Octopus reads like a fast-paced biography rather than a typical academic volume. What was it like embracing a nonacademic writing style?

I'm hoping to reach a broader audience than my previous books, which were pitched more for academics. This approach changed me forever. I had always thought that the scholarship or story draws people in. But I understand now that it's the way you tell a story. It's the way in which you build suspense, and how you set a scene. I'm also trying to strike overly academic explanations of things that really don't require that. And I take this approach now in almost everything I write.

One storytelling device I chose for the book is to refer to Eli Black not as Black, but as Eli, as if he were a personal friend. (And I feel like I did get to know him.) I use this device to draw people in and to present him as a fully fleshed-out person, with hopes and dreams. And I hope that this helps people connect to him.

Black's Jewish identity plays a central role in the book. He was a descendant of 10 generations of rabbis, and scenes in the book such as a Passover Seder at his family home convey him as engaged with Jewish life. How do you think he merged Jewish values with his role as CEO of United Brands?

I think that he took all the wisdom he received at Yeshiva University in becoming a rabbi, and piled it into the business project of United Brands. And I think that when he ultimately failed, not just in terms of the business failing, but in terms of following core Jewish tenets, it weighed heavily on him. (Paying a bribe to the president of Honduras to lower taxes on bananas had major implications for the social welfare of the people who worked for Black in Honduras.)

Looking back, I think that Eli Black left the rabbinate because of the Holocaust. It was April of 1945 when evidence of genocide was confirmed at Buchenwald. That shook him and later in his life he said that he was not convinced that he could change people's minds through sermons, and that he could do more good in the world through business.

I think the context suggests that it was more than just the failure of the business that caused his despair. It was his failure to live up to the principles that led him to choose business instead of the rabbinate in 1945.

The title of this book evokes a fable or fairy tale. What lessons do you think Black's story offers to leaders today who are trying to fuse business with social responsibility?

There's the idea that you have to honor the people who create the wealth of a company, not only through benefits packages, which Eli did, but also by embracing them as partners in the business venture. Eli did this to a point with both César Chavez and Oscar Gale Varela, a labor leader in Latin America.

But we can go further. At the end of the book, I point to examples of what it looks like to go all the way in with workers. For example, in Vermont, activists with Migrant Justice, an organization that promotes "worker-led social responsibility," collaborated with Ben and Jerry's to secure better working conditions on Vermont dairy farms. This program benefits the most vulnerable workers—mostly Latino laborers who have migrated all the way to Vermont to produce the milk and create the ice cream that we eat.

We're also seeing ESG in the news. (An acronym for Environmental, Social, and Governance, ESG helps potential investors understand a business's environmental and social risks as part of a broader financial analysis.) There are people in the Republican party who are criticizing ESG and blaming the current bank crisis on "woke capitalism," which you could argue started with Eli Black and evolved to business leaders today preaching the idea of social responsibility. Another reason this is a parable for our times is that we're now rethinking stock buybacks by companies, which Eli did later in his life to cater to shareholders.

There's suggested legislation by President Biden saying that the stock buyback tax should be higher. Recently, in his annual letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders, Warren Buffett suggested that critics of stock buybacks are "economic illiterates." Well, count me in as an economic illiterate because I don't see how these are benefiting our companies, or our society.

I hope that people take away from this book that Eli didn't go far enough. He compromised his own principles for the sake of serving shareholders first, and that's a mistake.