- About

- Departments & Programs

- Faculty Resources

- Governance

- Diversity

- News

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

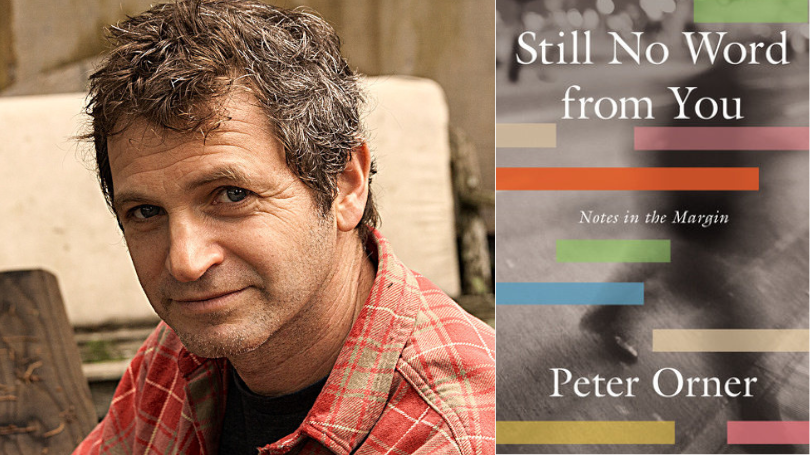

In Still No Word From You, professor Peter Orner weaves memories of family, love, and loss with reflections on why we read and write.

Peter Orner hadn't set out to write a nonfiction book. In fact, the professor and director of creative writing had been working on another project entirely when he realized his pandemic-fueled habit of writing notes on his latest reads was inspiring meaningful memories and questions on reading, writing, and life.

These thought-provoking annotations and personal stories evolved into Still No Word From You: Notes in the Margin, a collection of personal essays. The compilation draws on Orner's own memories of family, love, and loss.

For example, a note written by his mother in the margin of a book conjures a reflection on her youth in Chicago; a World War II plea from Orner's grandfather to his grandmother to reply to one of his letters inspires Orner's contemplation on the meaning of reading—and becomes the title for the book. Throughout the collection, Orner weaves in reflections on well-known authors such as Lorraine Hansberry and Primo Levi.

Still No Word From You has received starred reviews from both Publishers Weekly and Kirkus and was dubbed "an ideal autumn book" by the Chicago Tribune. Excerpts of the book have appeared in the Paris Review and are forthcoming in Harpers.

Orner is the author of two novels, three story collections, and a collection of essays, Am I Alone Here?, which was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for Criticism. He is a three-time recipient of the Pushcart Prize, winner of the Rome Prize from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and a recipient of both a Guggenheim Fellowship and a Fulbright. His work has appeared in The Best American Short Stories, The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and The Paris Review, among others.

Here, Orner talks about the inspiration for his new book and his advice for fellow readers.

You have said that you consider yourself primarily a fiction writer. How did this book come about?

Like a lot of my books, it came about by accident. It started with notes to myself about things I was reading just before and during the pandemic. It grew into this routine that I would engage in in the mornings—I would just take a few notes on what I was reading or thinking about. I'd read someone else's line and remember something from my own family. It just started to build; I started to see some connections between them. That's when it felt like, OK, maybe this is something.

How would you describe the book?

It's a memoir in reading, but a reluctant one. An attempt to mostly write about literature but there were times I couldn't help myself and had a few things to say about my own life.

Your book takes its title from a line your grandfather wrote to your grandmother in one of his letters to her during World War II. He'd been writing her daily and she rarely responded, prompting him finally to grumble, "Another day and still no word from you." You commented that perhaps the reason we read is to seek that word from someone, anyone. Can you elaborate on that?

I felt moved by trying to imagine my grandfather, who, in his early 40s, was too old for the war, very lonely out on the ship in the Pacific, and constantly writing these letters to my grandmother, who never wrote back. She was raising two kids, and was a professional dancer. She was too busy to respond, for good reason. She had her own life during the war as well. But it's something that intrigues me, the idea of this conversation that those two never actually had.

With books, we're having a conversation over space and time; say there's a writer who's been dead for a long time and, suddenly, you read them and their voice is right there. And you're not just passively absorbing it, you're having this strange exchange.

Speaking of conversation, you've said you like to think of Still No Word From You as a kind of intimate conversation with the reader. How does this conception of a book as a living, breathing thing inform your own approach to reading and writing?

I divide the world into people who write in their books and people who don't. I say write in the book. It's not sacred; if a book is any good, it's a living, breathing thing. You can talk back to it. It's not a gravestone. And I think people sometimes treat a book like it's dead, you know what I mean?

I'm always looking for things people write in the margins. My mother wrote a note in a margin of a Lawrence Ferlinghetti book of poems called A Coney Island of the Mind. I found it and I tried to imagine her as a much younger person, in the early 1960s in Chicago, being excited about the future.

What do you hope readers of Still No Word From You will come away with?

Something I hope people will take away from it is to slow down a little bit, especially when you read. Truly engage with the work instead. Turn off your critical mind machine a little. Read closely but generously. When I read something closely, if I'm truly engaged in a scene, it becomes a part of my own life. That, to me, is what I'm always looking for when I read. Not to be educated, not to be taught, not to be told by the writer what they know and what I don't—just to engage and feel it somehow.