Menu

- About

- Departments & Programs

- Faculty Resources

- Governance

- Diversity

- News

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

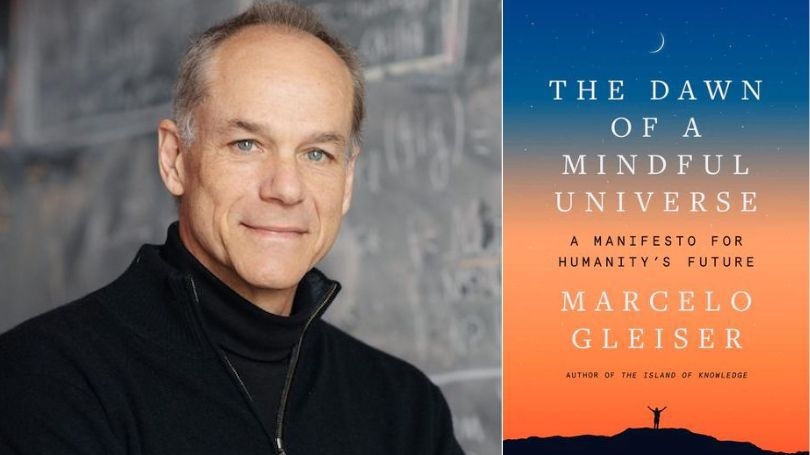

To address the climate crisis, we need to rethink our place in the cosmos, astrophysicist Marcelo Gleiser argues in his new book.

Marcelo Gleiser remembers the moment when his interest in the cosmos and the Big Bang veered back to Earth. The Dartmouth professor was fly fishing in Iceland and had just hooked a magnificent trout.

"Before I released it, I thought, who am I to inflict pain and suffering on such a beautiful creature?" he says. It was an epiphany that led Gleiser, an expert on the early universe and holder of the Appleton Professorship of Natural Philosophy, to abandon fly fishing for trail running, and to learn as much as he could about the origin and evolution of life.

"Chemicals organized themselves three-and-a-half billion years ago to become a living thing that can absorb energy and reproduce," he says. "This jump from nonlife to life is the biggest mystery, and it happened here."

In The Dawn of a Mindful Universe: A Manifesto for Humanity's Future, Gleiser translates this sense of awe into a call to action for taking better care of the planet. Despite a summer of record-setting heat in many parts of the world, Gleiser is optimistic that we can solve the climate crisis with a change in mindset, an argument he also makes for resolving the latest crisis in cosmology: Webb telescope images that contradict the prevailing view of how the universe formed.

"A revolution may end up being the best path to progress," he and physicist Adam Frank recently wrote in the New York Times.

A professor of physics and astronomy, Gleiser has authored five books and is the first Latin American and Dartmouth faculty member to receive the prestigious Templeton Prize, "a philanthropic catalyst for discoveries relating to the deepest and most perplexing questions facing humankind." In a Q&A, he shares insights on his new book, cosmic storytelling, and next big project.

What inspired this book?

After I received the Templeton Prize, I realized I could become a voice for changing our relationship to the planet, to advocate for what I call secular spirituality—being spiritual without embracing a religion. As you grow to understand the beauty and fragility of life on this planet, and our deep interdependence, you develop a sense of the sacred. When I'm running on the Appalachian Trail, it's a primal feeling being deeply connected to the land, to the forest. That's my way of worshiping the world.

You're a theoretical physicist. Is this your first manifesto?

Well, yes, I'd never written a manifesto before! So, I went back to my teenage years to reread Marx and Engel's Communist Manifesto, which changed many countries. It essentially has two parts: the argument itself, why the change is needed, and how you implement the change, action items that groups and individuals should take. My call-to-action items hinge on reframing the way we relate to life on the planet and to others, hopefully in a powerful way that will inspire people.

Why is change needed?

Civilization is on an unsustainable path. Climate change is a serious existential problem that we've barely started to address. Why? Because we believe deeply, culturally, viscerally that we own the place. We take what we need, without any concern for the repercussions. That worked fine for about 200 years since the industrial revolution, but it doesn't anymore. Our species is now at a crossroads. Our actions are so destructive and so global in reach that we are now on a suicidal path. The notion that we might colonize Mars and find another home in space because we messed up this world is ridiculous and morally depressing.

What's the solution?

We need to change our mindset and recognize that we are not above nature; we are part of it. I call this biocentrism, the concept that our planet is a sacred world that needs to be protected and respected.

Think of the pandemic. Yes, vaccines helped to shorten it and reduce the number of deaths. But we were reactive. Many Indigenous cultures have a sacred relation to the planet. They respect it, revere it, and are grateful for what it has given us: the opportunity to be ourselves. Without air, water, and a stable climate we wouldn't be here. For 95% of human history—about the last 300,000 years or so—we lived in a completely different way than we do now. Our ancestors were in dialogue with nature. Then, 12,000 years ago, we became an agrarian civilization and tried to tame nature to serve our own purposes.

Farming changed our relationship to nature. When did our cosmic view shift?

In 1543, Copernicus showed that the Earth is not the center of the universe. It's just a planet, like other planets. The more we learned about stars and galaxies, the less important we became. What I tried to show in the book is that we are incredibly important. Our planet is a rare oasis in a universe hostile to life. If you look at other planets, there's nothing like Earth. Life has been around for 3.5 billion years and 3 billion years of that was just bacteria. The odds of finding complex, intelligent life out there are minuscule. We are a living world among many dead worlds.

So, from a life point of view, Earth is the center?

It's why I call this a post-Copernican idea. We are the agglomeration of molecules that can tell stories about who we are. Maybe whales tell stories, but we are the ones that debate the meaning of our existence. We are, in a sense, how the universe is telling its own story. We are the cosmic storytellers, and so, we are cosmically important. Without us and Earth, the universe would have no voice. It would be a conglomeration of stars and planets being born and disappearing. What I'm trying to do is wake people up. Even if there are other intelligences out there telling stories, this is our story. And that's the core of the biocentric argument.

Are biocentrism and capitalism incompatible?

The incompatibility only comes when capitalism becomes immoral. There's no reason why respecting the planet needs to be anti-progress. It's quite the opposite. To make progress with the planet, we need to rethink how we sustain our civilization. Instead of eating up what's underground, the oil, gas, and coal that fuel our civilization, why not gather what's coming down from the sky, the sun and wind? It's a switch from predatory to regenerative, and corporations can be part of it.

What are some practical ways people can be more biocentric?

You make choices about how you live that mirror your value system. If your values are aligned with a better planet, your choices will reflect that. I call it the mindful approach to consumerism: less meat, less energy, less water, less garbage, more engagement with the natural world.

Go out into the world and rejoice in nature. Go forest bathing, have a bonsai tree in your apartment, do tai chi in the park. Pay attention to the trees, the clouds, the sky. Stop buying from companies that don't align with your values. The beauty of capitalism is that companies respond if people stop buying their products. In the Communist Manifesto, they say, "Workers of the world, unite." Here I say, "Consumers of the world, unite."

What's next?

What I have done, with my wife, is to buy a 15th-century villa in Tuscany that comes with a beautiful church. We plan to repurpose it to become a think tank for scientists, philosophers, artists, intellectuals, and journalists, to talk about the big questions of the world. That will be my next big thing.